Report : Mondial du Tatouage 2018

Text : DHK

Le Mondial du Tatouage 2018: the postponement! ATC Tattoo is at the Hall de la Villette for the tattoo convention of the Mondial du Tatouage 2018. There are more than 300 tattoo artists but also a nice quantity of tattoos pricked. The whole, during this weekend of March.

A tattoo convention like few others. The Tattoo World 2018, will have once again this year, filled our eyes. With a tired body and a smile on our lips, we're determined to go back to the Hall de la Villette next year!

Find this article in full, photographs and tattoos, on the application

ATC Tattoo

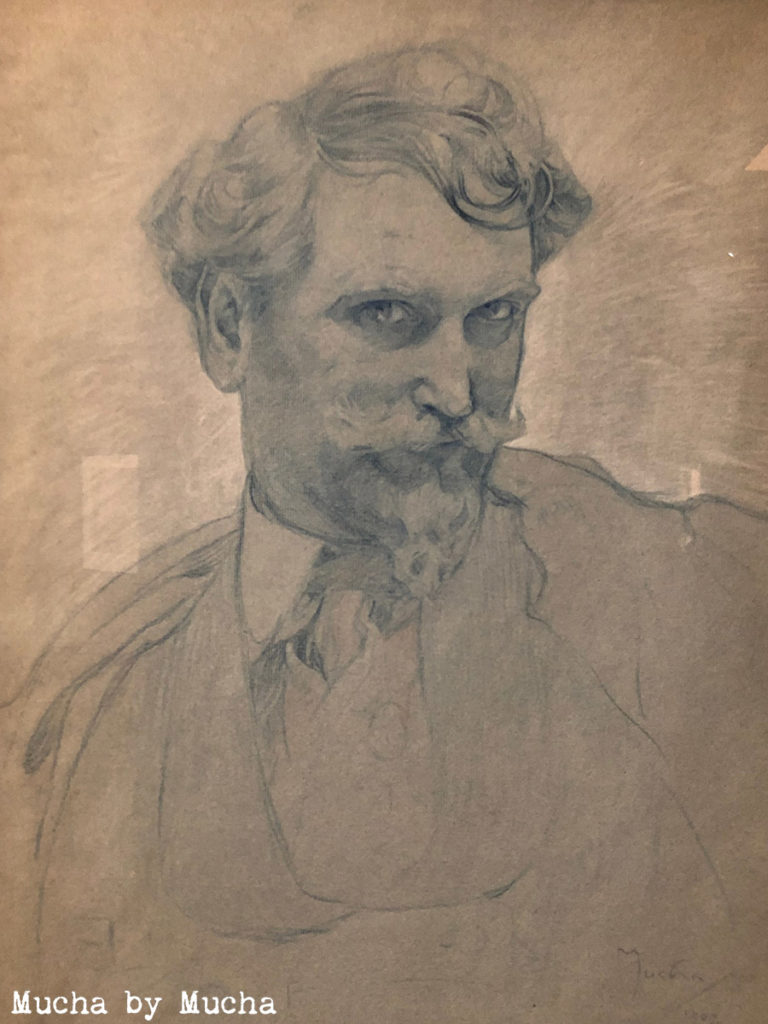

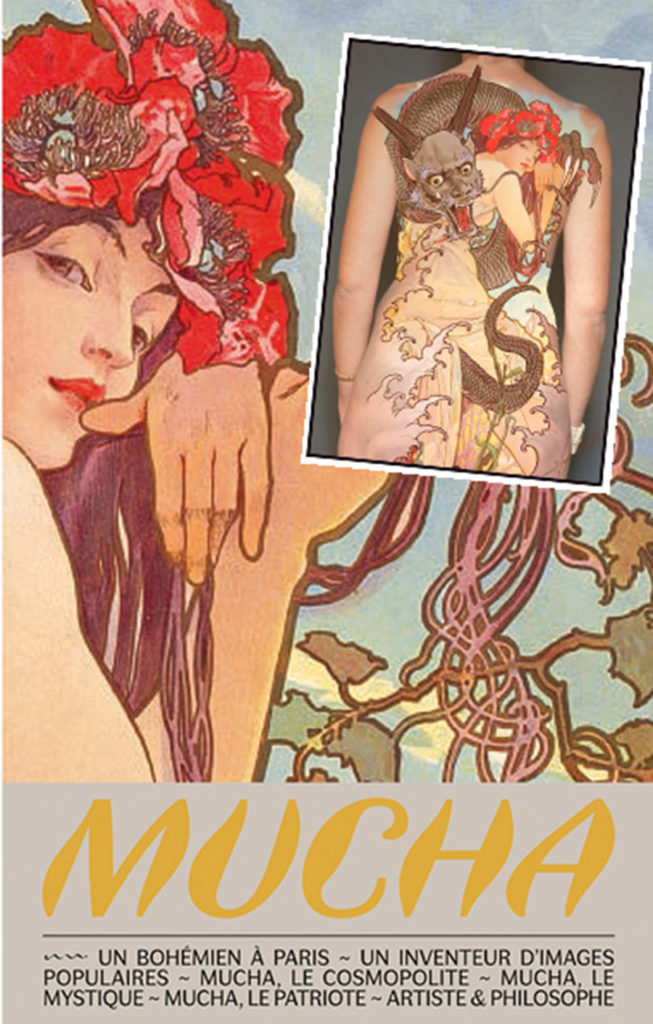

The tattoo in honnour of Alphonse Mucha

Par DHK

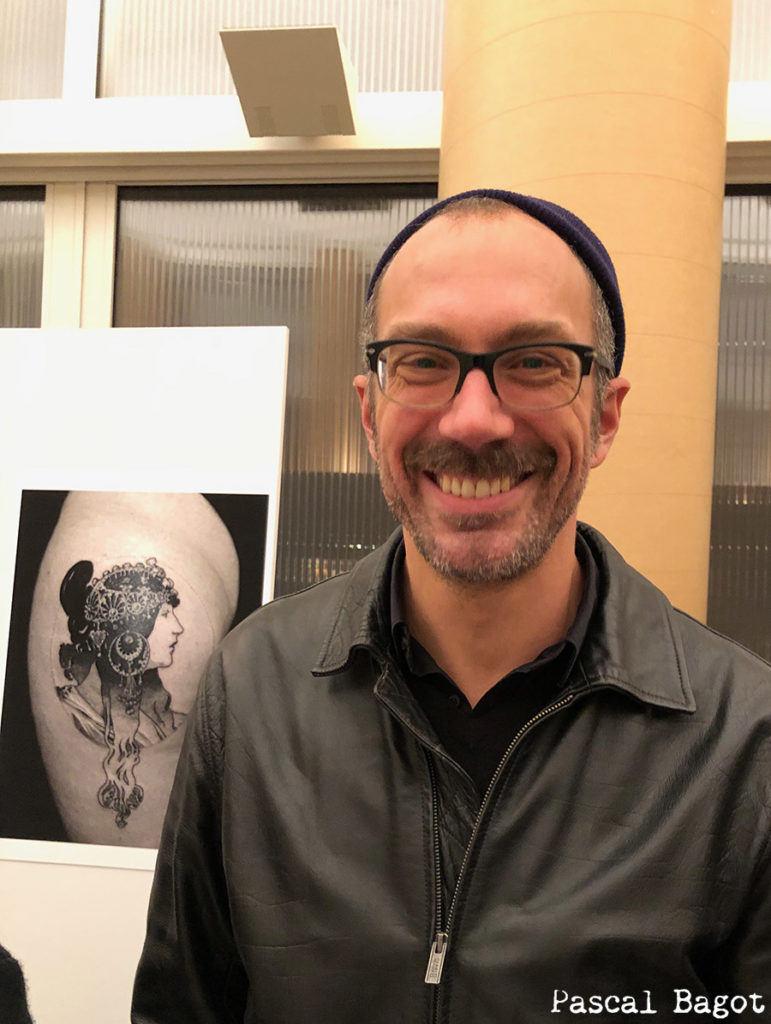

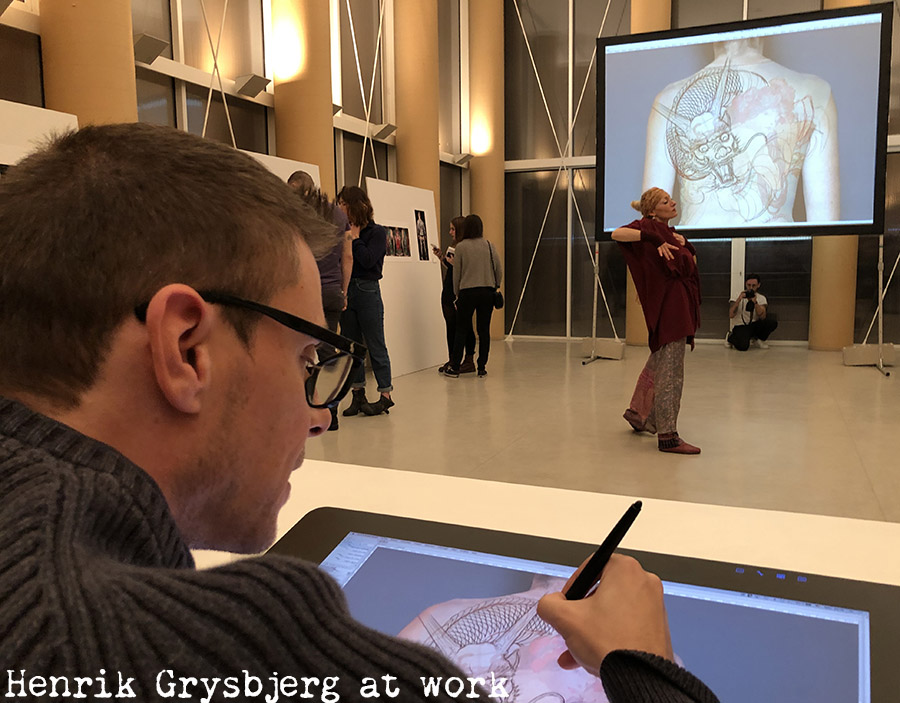

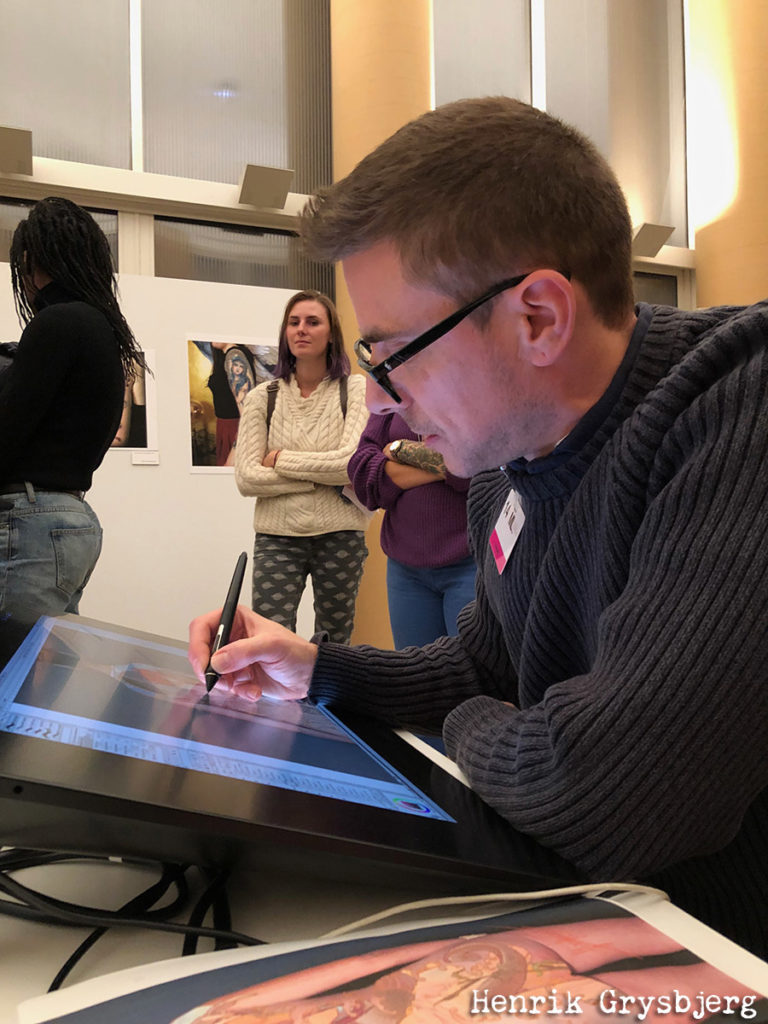

On Pascal Bagot’s initiative, a journalist specialisedin the tattoo press, the idea to invite tattoo artists totake over the museumin the 6thdistrictof Paris was born. A short-livedexhibition of tattoo photos on the theme of Mucha and a performance by Henrik Grysbjerg was organized for theoccasion. (Saturday november 24, 2018)

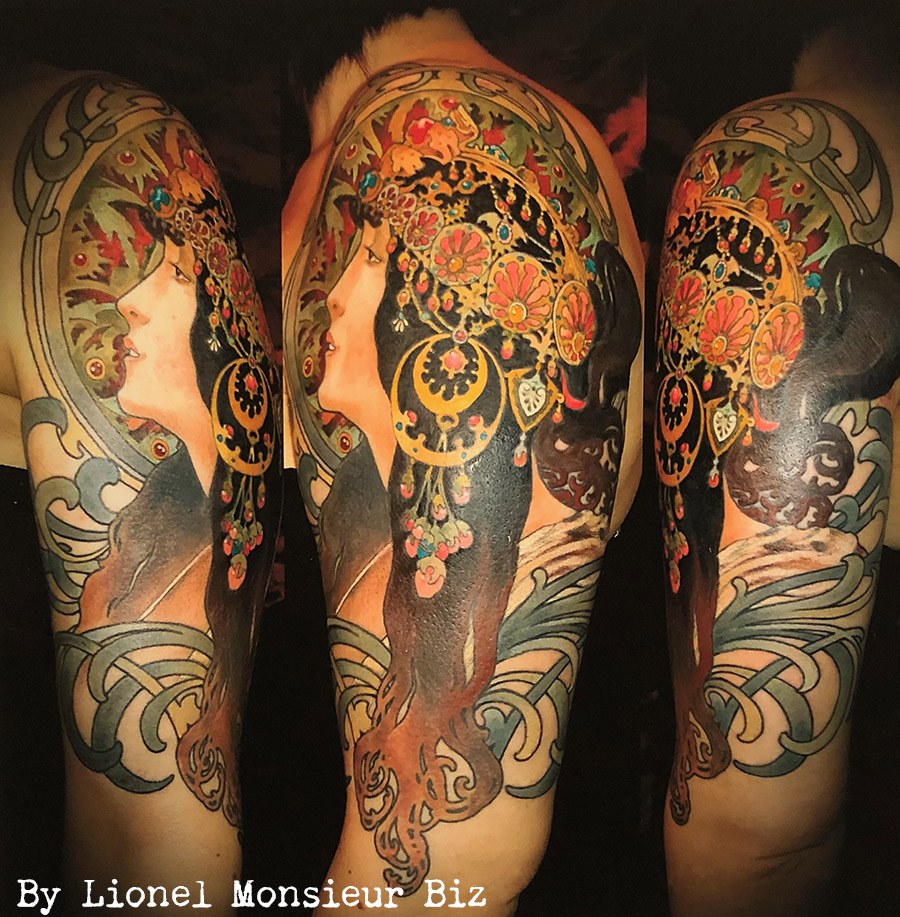

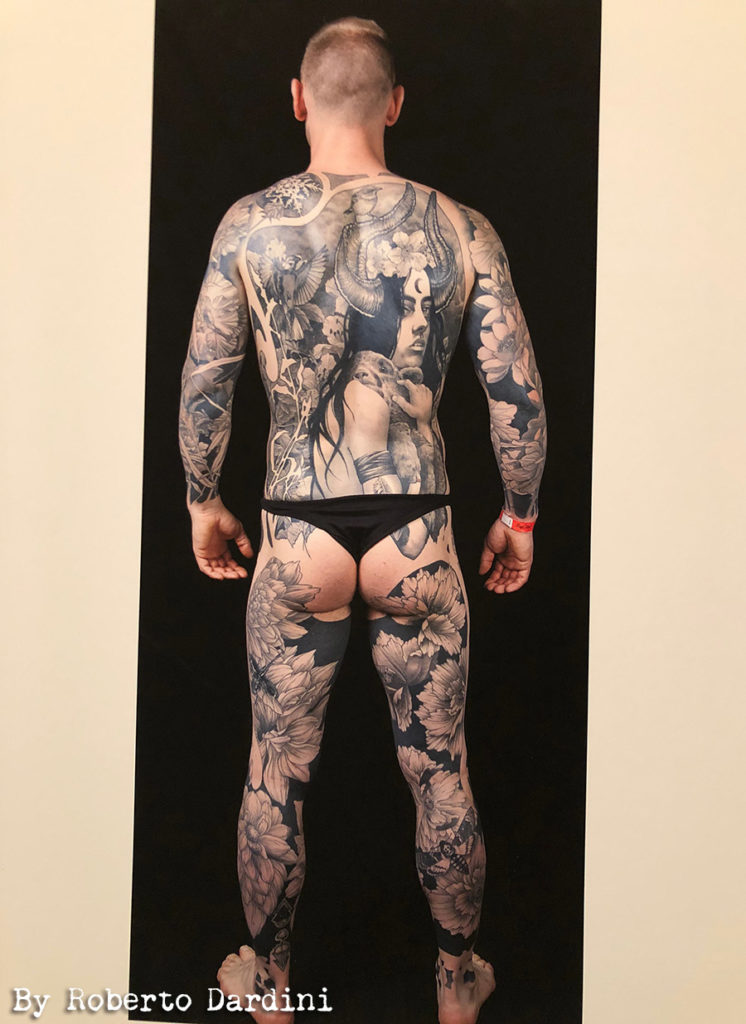

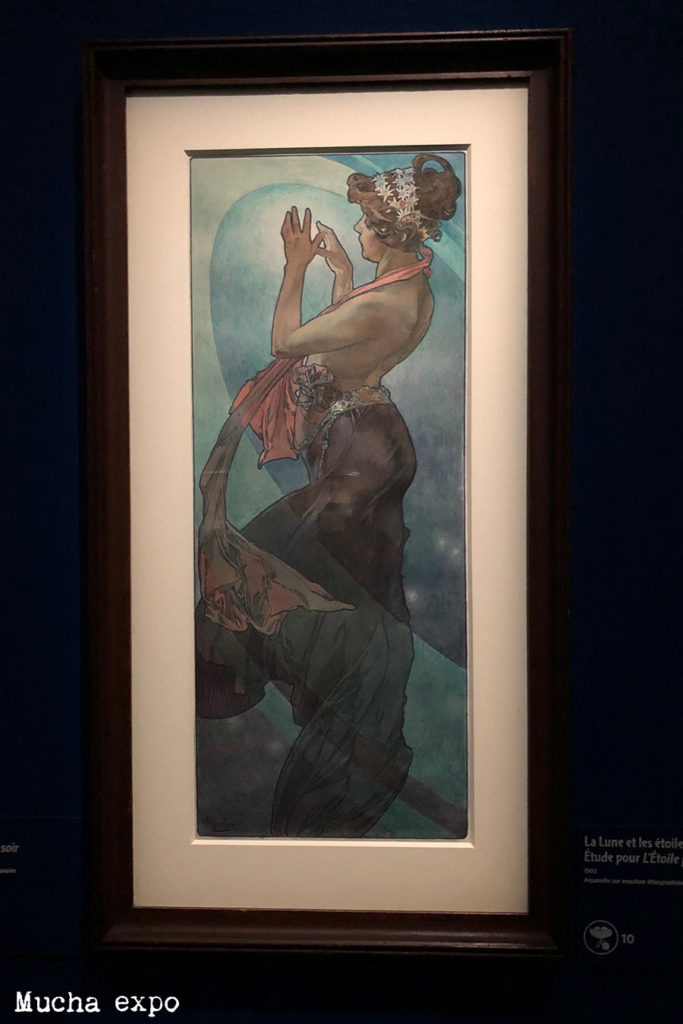

Alphonse Mucha is a painter, poster designer and illustrator of Czech origin from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He became famousby creating posters for Sarah Bernhardt's shows and later on was the most recognized Art Nouveau artist.His drawings, which havestrong lines and background ornaments, are a perfect match for tattoos.Atattoo, in order to endure timeand sunlight,needs contrast and clear lines. Muchabecomesa real source of inspiration for tattoo artistsall over the world. And the many works presented at theevent prove it.

On this occasion a performance around tattooing was realized by Henrik Grysbjerg,afamous tattoo artist from Toulouse. For nearly three hours he customized the exhibition’sposter with a superb Japanese dragon using a graphic tablet projected on a large screen.

Mucha and tattoo

In addition to Alphonse Mucha's superb exhibition, we were able to admire photos of tattoos madeby Samoth, Lionel Mr Biz, Alix Gé, Roberto Dardini, Easy Sacha among others. Many tattoo artists were there regardless of wether they were participating in the event or not. A very nice evening which also allowed us to visit the Mucha exhibition. Our thanksgoto Pascal Bagot for thisgreat moment.

FIND THIS ARTICLE IN FULL, PHOTOGRAPHS AND TATTOOS, ON THE APPLICATION

ATC TATTOO

Hommage au Népal meurtri

Text : Laure Siegel / Photographies : P-mod / Tom Vater

Bhaktapur, historic city in Kathmandu valley, deux dys before the earthquake

Many tattooists and travelers on the Asian roads were looking forward to participate in the 5th International Tattoo Convention in Kathmandu, Nepal, a special event in the global tattoo scene calendar. But the giant earthquake that shook the country around lunch time on Saturday, April 25th ended the convention prematurely.

More than 8700 people lost their lives, half a million homes were destroyed, entire villages have disappeared, more than a quarter of the country’s population, some 8 million people were directly affected by the catastrophe. The already desperate situation was further aggravated by countless aftershocks and a second strong quake on May 12th.

Some of the participating artists chose to remain in Nepal to lend a hand with relief projects or helped raise funds for Nepalese affected by the quake - projects that readers of Skin Deep can support.

The 5th International Nepal Tattoo Convention : Never say never again

The ballroom of the Yak and Yeti hotel saw its first visitors in 1953, the year the mythical Himalayan kingdom first opened its temples and palaces to the world. Two generations later, the luxury caravansary in the heart of the Nepalese capital is hosting the fifth International Nepal Tattoo Convention, only to be severely shaken by the earthquake. But in spite of the catastrophe, the convention’s organizers are not giving up.

On Friday morning, April 24th, Swiss tattooist Johann Morel (Steel Work Shop) sat waiting for his first customers, his flashes on the table in front of him, “I am really looking forward to doing work here because I will donate all the money I make to Saathi, an association which helps women and children in Kathmandu. I don’t need the money; right after the convention I have a guest spot in Hong Kong and back home in Switzerland I have a twelve month waiting list. I charge 20 GBP a tattoo and I hope that I can raise at least 350 GBP. I’ve never felt so welcome at a tattoo convention and Mohan Gurung’s team, the organizers, is amazing.”

For most participating artists, Nepal is ‘different’. Many of the attending tattooists live on the road and they don’t come for business – Nepal is a poor country and Nepalese can’t afford international tattoo rates – but for the experience. In the last few years, Kathmandu has become the ‘cool’ convention: You can hippie around in bare feet on the hotel’s terrace with artists and punters who have managed to cross the highest mountain range in the world to get here.

Serjiu Arnautu, young roumanian tattooist, just openened a tattoo shop in Dijon (France). He was at the Kathmandu tattoo convention with his friend Tessa Marx (Boubou Daikini), who's doing traditionnal handpoking.

The event is popular with a diverse crowd – tourists, trekkers, adherents of the Goa trance scene and UN diplomats as well as local families and groups of young Nepalese – because of its effervescent ambience; it’s no longer the domain of shady Kathmandu gangsters and hard men. Nepalese society has become more open to global counter culture in recent years. There’s room for self expression in early 21st century Nepal.

While children in ethnic costumes handed out flower petals to visitors and traditional dancers graced the convention’s stage, a crowd of curious onlookers gathered around the stall of Iestyn Flye (Divine Canvas) as the British artist who specializes in scarification etched a design onto the chest of a young Nepalese who sat through the ordeal with gritted teeth.

Eric Jason D Souza (Iron Buzz Tattoos) won the first price of the first day’s contest for a portrait of a women inked on his partner’s forearm.

Aishin par Eric Jason Dsouza, Iron buzz-tattoos (India) Best of small

The young couple who traveled from Mumbai for the third year running was ecstatic. “It’s great to be recognized here because tattooing in India still struggles with quality issues. For the past two or three years, there’s been a huge tattoo boom in India and there are some 15.000 shops but only about 150 professional artists. We work hard on a project with the local government to make tattooing a more professional career choice.”

MaxWell

Arne inked by Dasha, on the road

Quentin Inglis getting a Sak Yant by Triangle Ink, Thaïland

Mia inked by Tattoo Junction, Kathmandu

Laura inked by Miraj, KTM Tattoo, Kathmandu

Black Ink power, japan

Neil inked by Glen Cozen, UK

Jesse inked by Daan Van Dobbelsteen - Dice Tattoo, NL

Arm in progress by MaxWell

Gabriel inked by Malika - tatouage Royale, Montréal, QC

Guy le Tatooer, few minutes before the earthquake...

On Saturday morning, April 25th, French artist Guy le Tatooer, who has spent his working life on the road, was slowly warming up to the convention scene. “I started attending these events for the first time this year – I will be in Borneo, in London and in Florence in the coming months. Here in Nepal, it’s mostly the local musicians who want tattoos. They are very open and want to have fun as in any society where the voice of the youth has been muzzled for too long. If the work is well done, the Nepalese, a highly artistic people, appreciate it.”

As Guy finished his sentence, the lights in the ballroom went off, a second later everything started to shake violently. Artists, punters and hotel staff stampeded from the room or tried to find shelter under door frames as stalls collapsed. The quake rattled on for 80 seconds. By the time the earth had stopped shaking, the entire convention found itself in the hotel car park watching the cracks in the Yak and Yeti’s façade, deep in shock but happy to be alive. Ajarn Man, a Thai sak yant tattoo master handed out Buddhist clay amulets for good luck.

The event after the earthquake

The days following the quake were harsh – countless aftershocks, tense streets, a dazed population, and periodic phone and Internet shut downs created incredible despair and sadness in the Nepalese capital. Some fifteen tattoo artists chose to stay in the city to try and help with relief operations and to support their local friends. Several artists traveled to Pashupatinath, the sacred Hindu temple complex on the shores of the Bagmati River to tattoo Nepalese who were seeking protection, against a backdrop of long rows of funeral pyres where families brought loved ones they had lost in the quake.

Paulo et Ari, ttattoo artists, welcome nepaleses looking for a protextion tattoo on a rock front of the Bagmati river, carring death's ashes de Kathmandu along.

Other artists raised funds to buy emergency supplies or to contribute to projects set up to construct toilets and temporary shelters in villages around the Kathmandu Valley. In New York, London, Copenhagen, Bangkok, Southampton, Les Vans, Rottweil and other cities around the world, local tattooists began to organize events to help finance reconstruction efforts.

French tattooists Max Well and Angie stayed on for two weeks before moving on to work at Six Fathoms Deep in Bangkok, Thailand. [IMAGE29] “We first came to Nepal for last year’s convention and it really changed our lives. The event has a real magic, it feels like one great family. We will go back soon, we have to finish the tattoos we started there. In the meantime we try to help from a distance by sending money. And if the convention returns next year we will be there.”

Mohan Gurung and Bijay Shrestha, the convention’s organizers, remain determined. “We are sure we will host the convention again next year. We know we will, with all the overwhelming support we got from the tattoo community, for us and for Nepal. We must continue this family tradition forever.”

How to help Nepal?

If you know any Nepalese, you can send them money directly by Western Union. Sinon, privilégiez un collectif de bénévoles qui agit directement sur le terrain ou participez à une action artistique :

#We Help Nepal

> #We Help Nepal : Un réseau sans hiérarchie et sans salaires, fondé par des Népalais et étrangers vivant ou ayant vécu au Népal. Ils se chargent de coordonner les initiatives locales en redistribuant les fonds récoltés via leur plateforme. http://www.wehelpnepal.org/

> Rise for Nepal : Une organisation créée par 200 jeunes volontaires népalais pour reconstruire leurs pays eux-mêmes, sur le terrain. https://www.facebook.com/pages/Rise-For-Nepal/1440722356239673

> Miranda Morton Yap, une écrivaine américaine qui vit à Katmandou et coordonne la levée de fonds pour Helter Shelter et To Da Loo, qui se concentrent sur la construction d'abris et de toilettes.

http://mirandatravelsblog.blogspot.com/2015/05/subject-rebuilding-nepal.html

Paying homage to Nepal: Tattoo artists, in solidarity with each other

With tattoo artist

> By Steel Work Shop (Switzerland) : No silence for NEPAL Association

https://www.facebook.com/nosilencefornepal/ - http://www.nosilence4nepal.com/

One Tattoo for Nepal : https://www.facebook.com/onetattofornepal

Metal for Nepal Tour : https://www.facebook.com/metal4nepal

> By Jad's Tattoo (Kathmandu) : Ktm-20152504

https://www.facebook.com/Ktm20152504 - http://www.gofundme.com/tdq7q8z4

> By Funky Buddha Tattoo (Kathmandu) : Funky Buddha Hands

http://www.facebook.com/FunkyBuddhaHands - http://www.leetchi.com/c/solidarite-de-nepal-3409692

> By Phil & Joanna Antahkarana (Copenhagen) : Tattoo Aid for Nepal, which helps fund Direct Relief, an NGO focusing on medical emergencies.

http://theantahkarana.tattoo/news.html

http://www.directrelief.org/

http://theantahkarana.tattoo/news.html

FIND THIS ARTICLE IN FULL, PHOTOGRAPHS AND TATTOOS, ON THE APPLICATION

ATC TATTOO

Berber Tattooing In Morocco's Middle Atlas

Text : Tiphaine Deraison / Visuels : Leu Family ©Seedpress

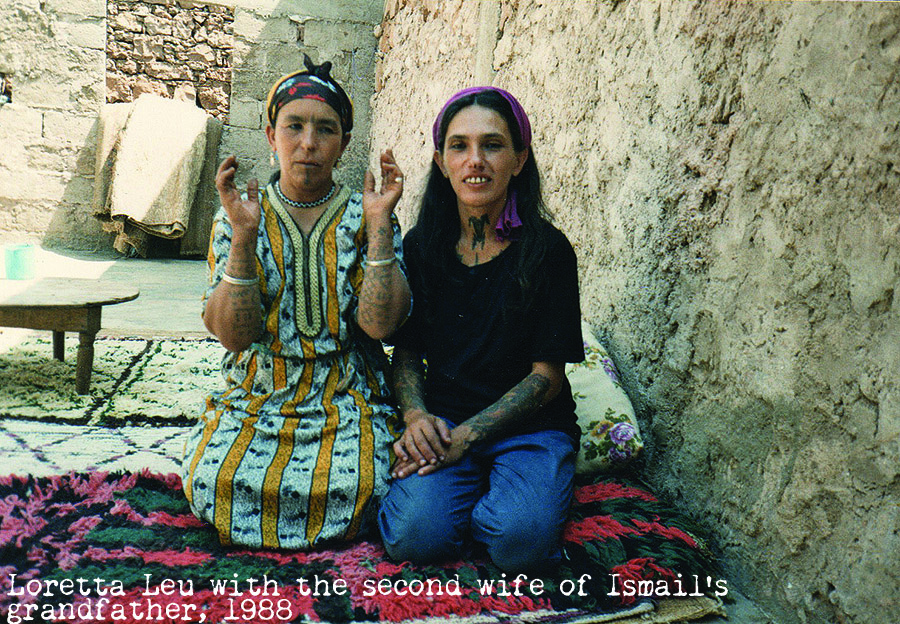

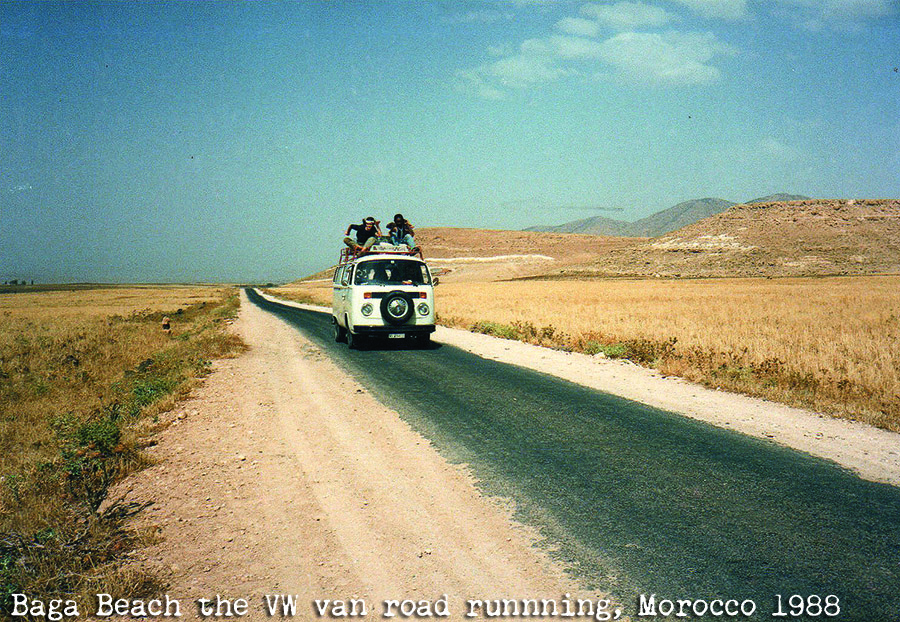

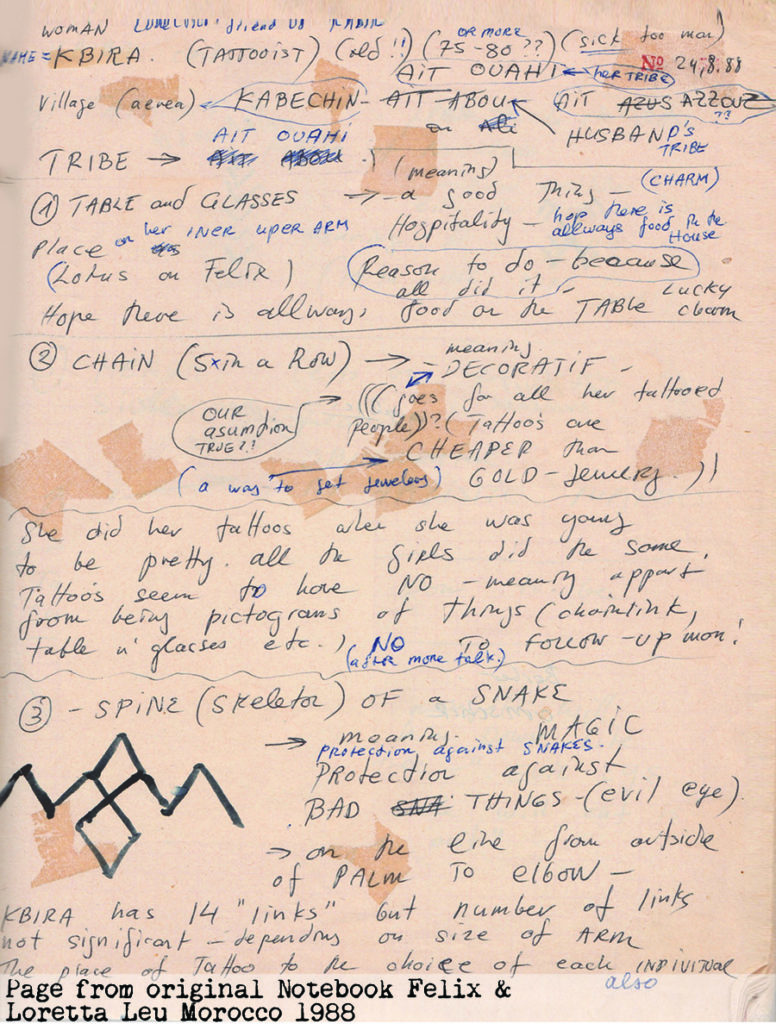

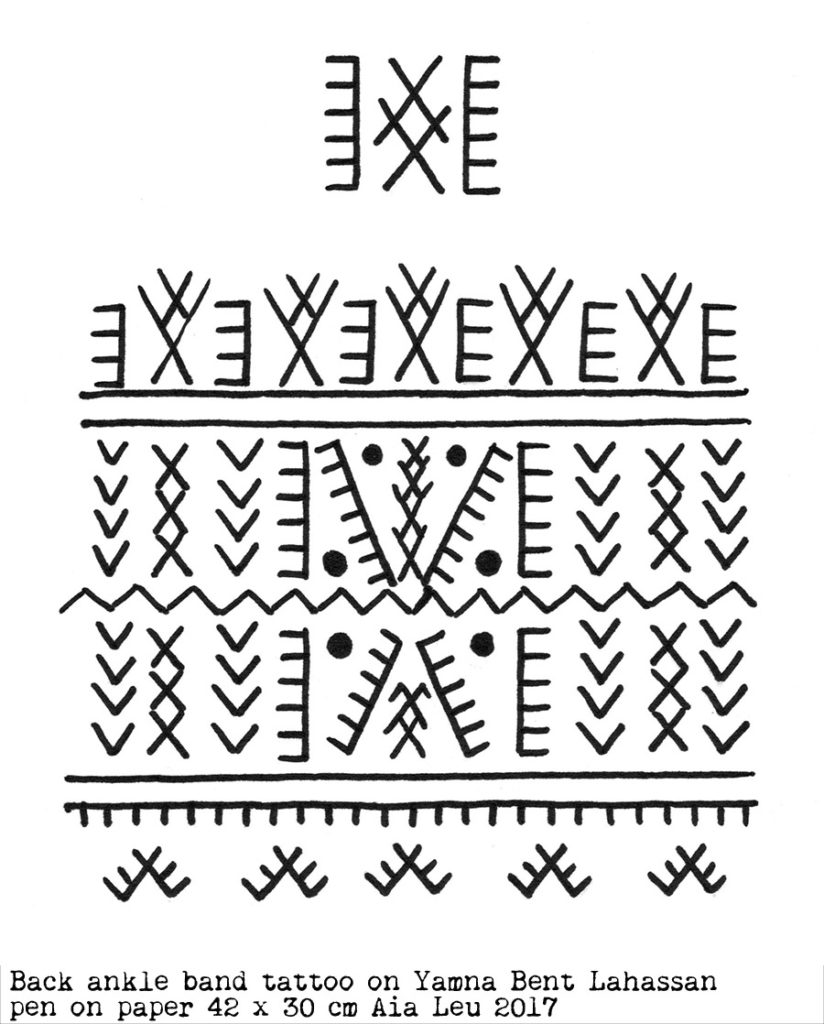

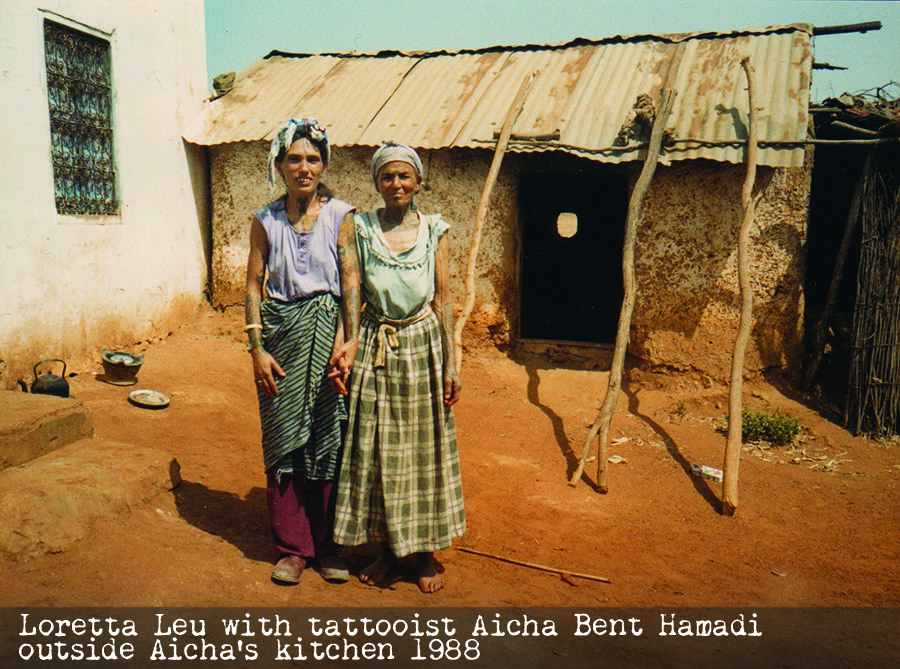

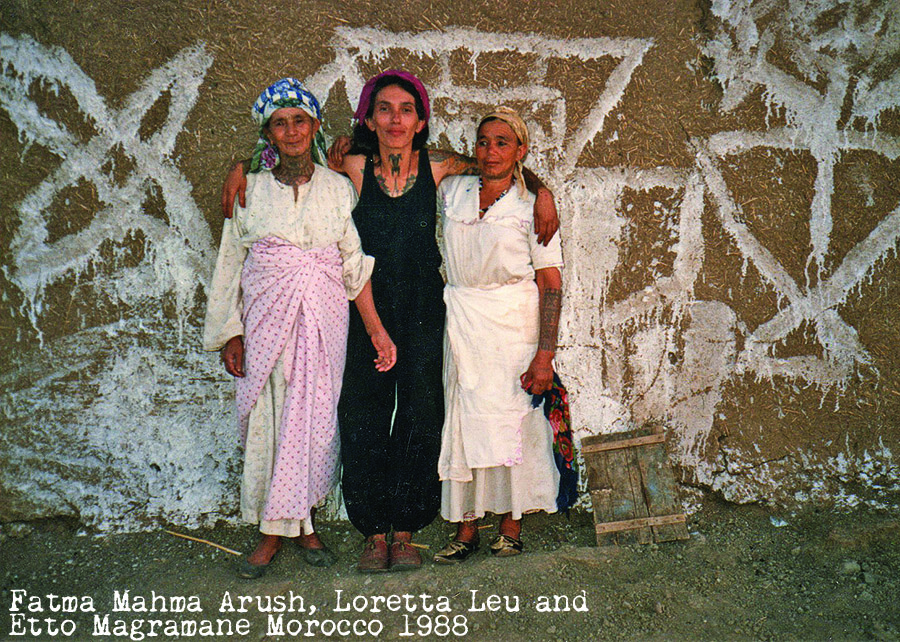

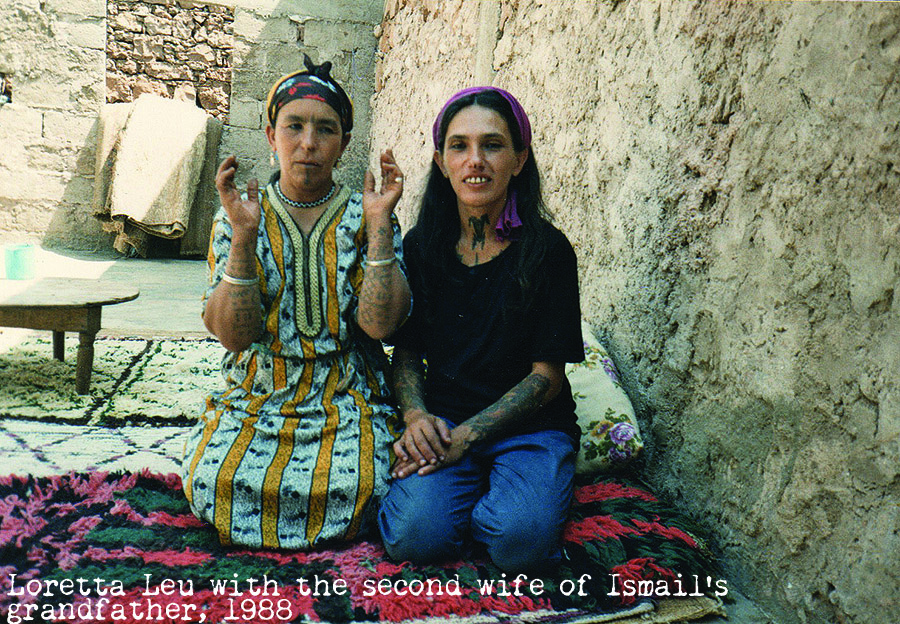

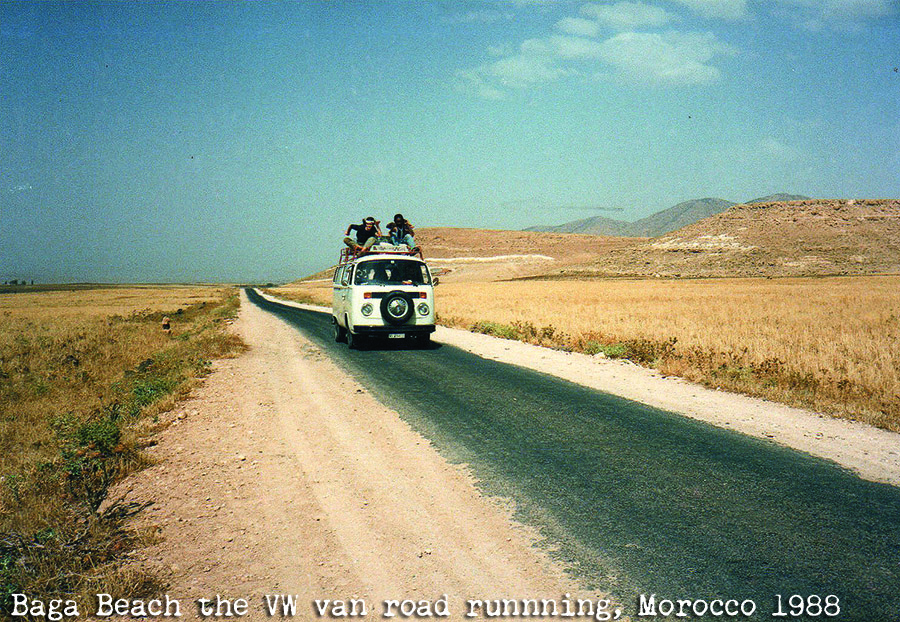

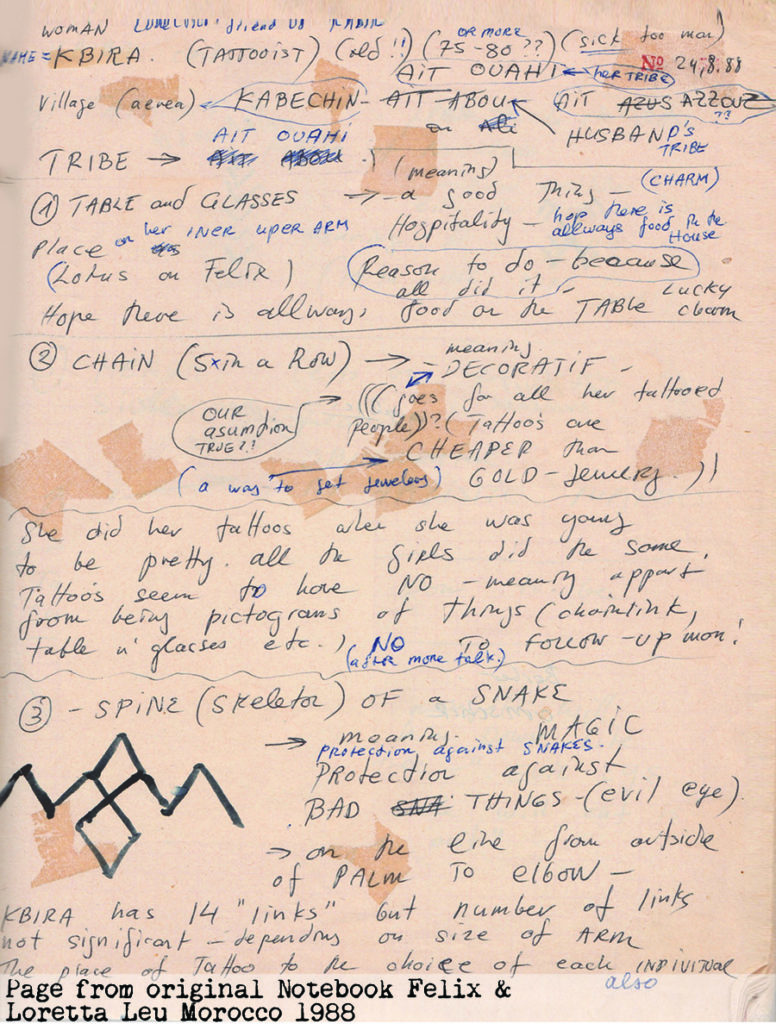

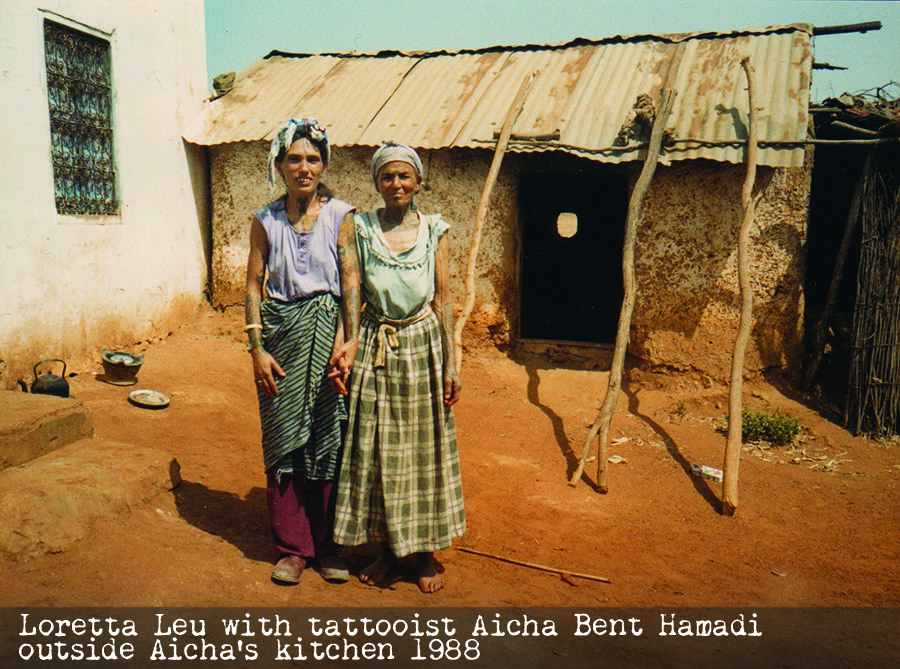

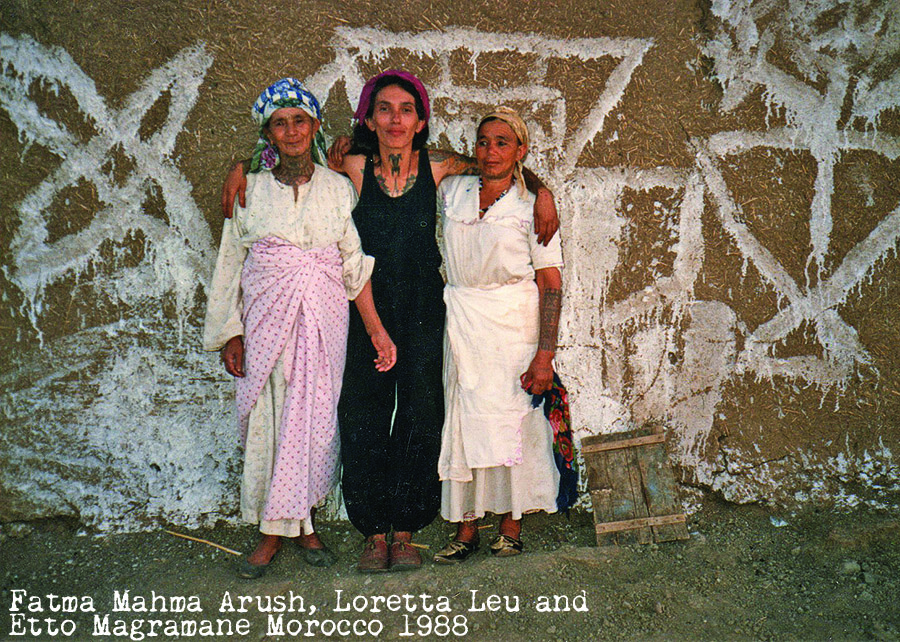

Immersing a rare detailed in the art of Moroccan Berber tattooing, "Berber Tattooing" is a unique testimony and the result of a series of chance encounters scattered in a story of adventures lived by a family well known in the Tattoo community. A story of Felix and Loretta Leu's journey in 1988, about thirty years ago in a rural and intimate world of Berber tribal women.

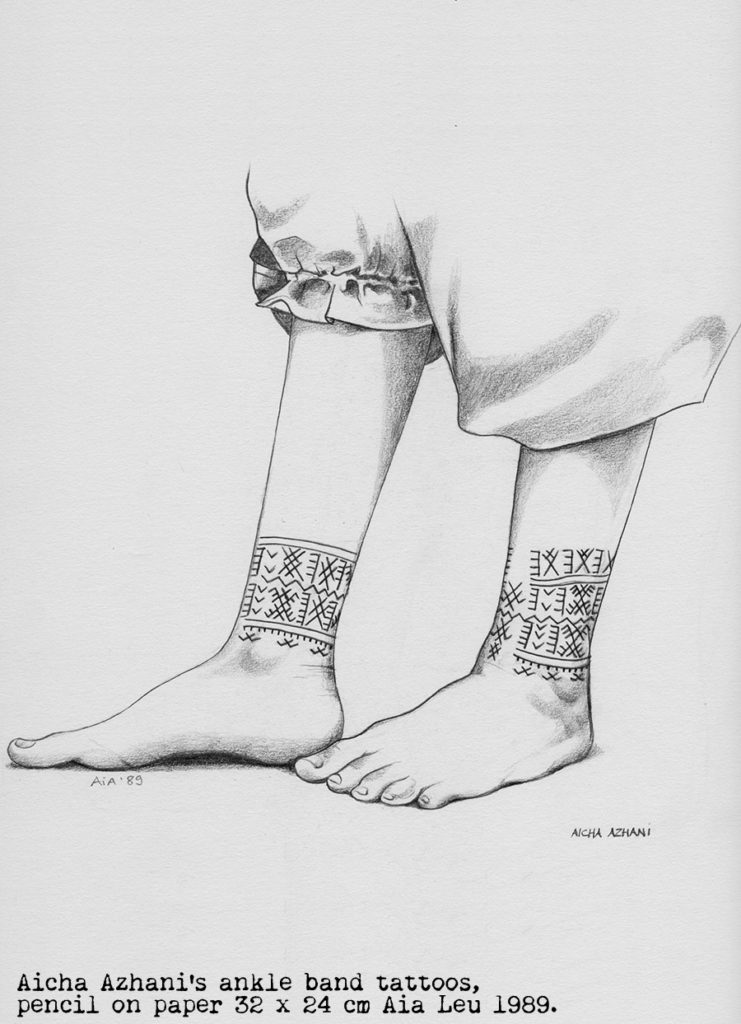

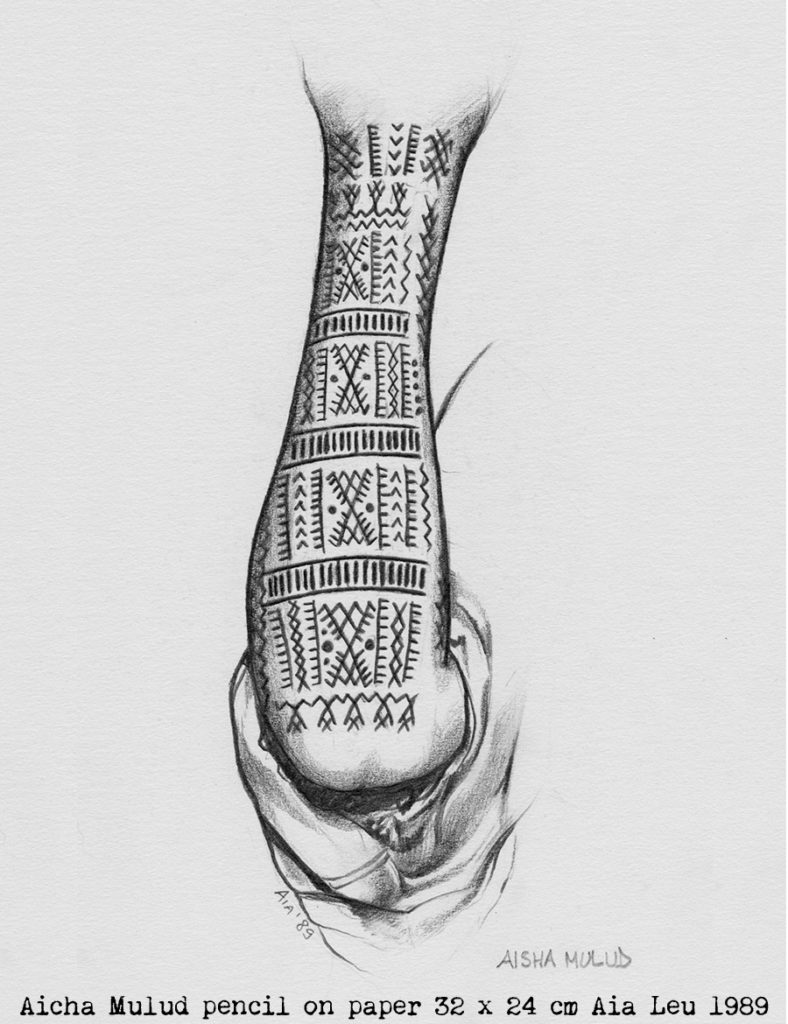

In 1988, when the Leu family first set foot in the Moroccan Atlas, they were welcomed by a local family, their only way to keep track of the art they witnessed was to learn, reproduce and draw these tattoos but also to understand their meaning and the history transmitted.

Berber Tattooing : an oral tradition of tattooing

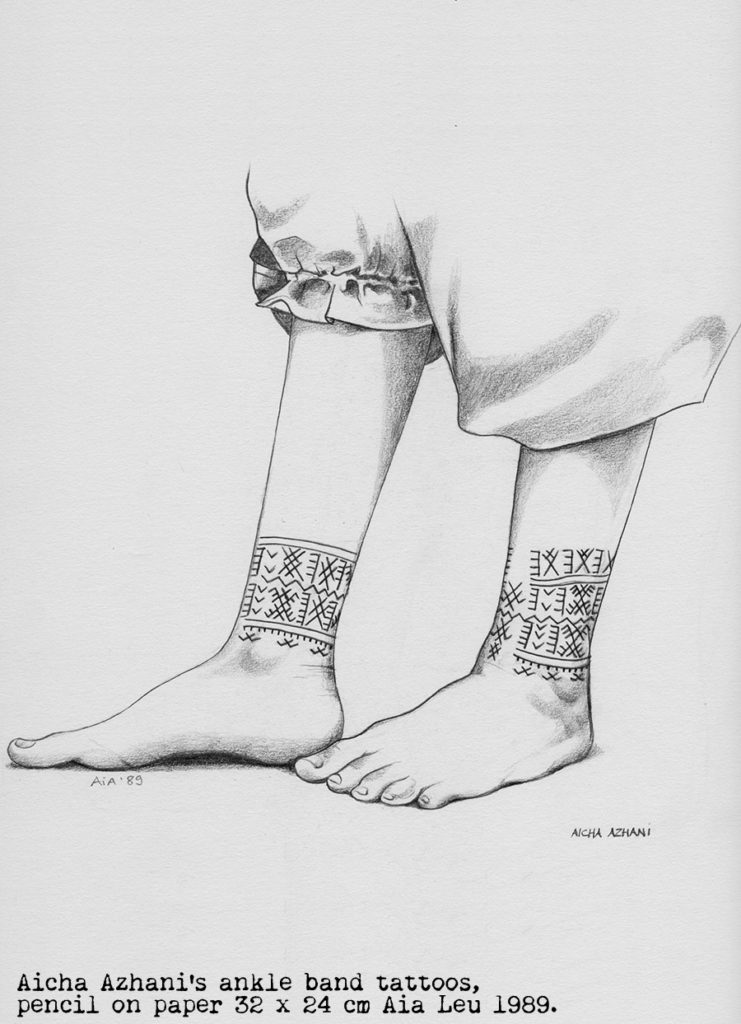

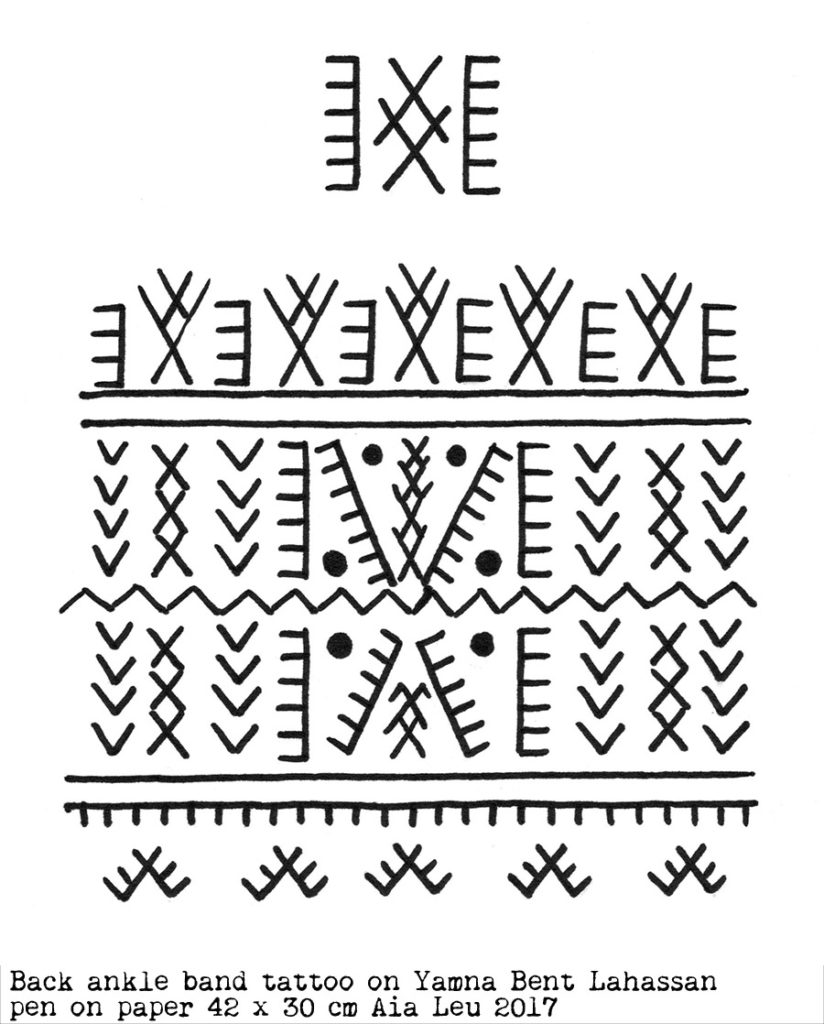

Only the oral tradition delivered from woman to woman and then the drawings of Aia Leu collected allow a thorough study of this art, ancestral art that Berber women perpetuate. A traditional tattoo that is part of their culture and daily life and captured with sensitivity in this book. Because this art is disappearing. Little documented, it is also less and less practiced today. Only the oldest generations are still the guardians of this invaluable knowledge.

A tribute to tattooing, the family, art and these women resulting from the travels of Felix and Loretta Leu, a family of artists, who discovered tattooing in 1978, the book is a unique source of documentation.

Berber Tattooing In Morocco's Middle Atlas

Felix & Loretta Leu

Illustrations par Aia Leu

Publié le 16 Novembre 2017

50 photos couleur 37 illustrations

42€

FIND THIS ARTICLE IN FULL, PHOTOGRAPHS AND TATTOOS, ABOUT THE APPLICATION

ATC TATTOO

My body, my passport

Part. 1 Borneo Ibans build the tattooing tradition revival.

Text : Laure Siegel - Photographies : P-Mod - Translation by Armelle Boussidan (Bornéo, Décembre 2015)

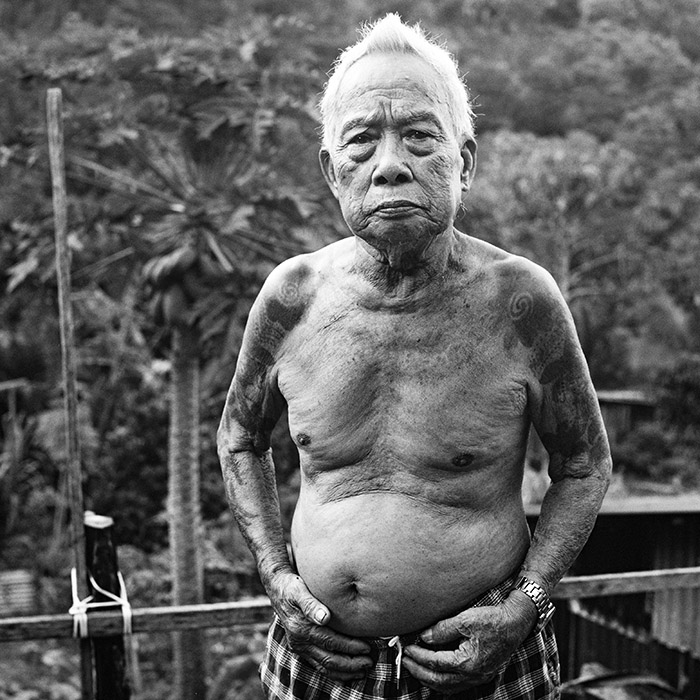

A people of pirates, head hunters, lumberjacks, planters and tireless travellers, Borneo's Ibans revive the tattootradition in order to recovertheir identity, lost in the limbos of history. We met the elders, whose armours of patang or kelingai - tattoos in the local language - represent roadmaps as much as a spiritual protections.

The tropical night has fallen onto the dense jungle as our canoe touches the sand bank. At this hour, only the python's whistles, the sound of the wind, the tinkling of glasses filled with langkao - the local rice alcohol- , the squeaking of Filipino fags and stories of days gone by, may break the silence. The members of the Iban ethnic group traditionally live in longhouses, big wooden houses on stilts which stretch along a mutual corridor and shelter about 25 families.

Some of them are only accessible via the river, since there is no road or since the existing road is regularly blocked by mudslides. Each longhouse has a representative, a tuai rumah, who gives their name to the village. Here, US is not the acronym for the United States, it rather means Ulu Skrang, the zone above the river Skrang. For administrative convenience after independence, the Malaysian government gathered several tribes under the name Iban, which comprises at least seven sub-groups, each with their own dialect, including the Skrang.

Ibans, also called the Sea Skrang, represent a third of the population of the state of Sarawak. From Java and the Chinese Yunnan, Ibans arrived during the XVIth Century via Kalimantan, a now Indonesian province south of Borneo. Loyal to their reputation of being fierce conquerors, they quickly dominated the other tribes of the fourth largest island in the world, and incidentally adopted and adapted their various tattooing traditions. Sat on a braided straw mattress in Mejong's longhouse, a four hours jeep drive from Kuching, Maja, an old man with very clear blue eyes tells us stories.

Villagers call him " Apai Jantai", Father of Jantai. At the end of world war II he was sent by the government in the neighbouring State of Sabah and then in the protectorate of the Sultanate of Brunei to work as a lumberjack. It was the only conceivable job for the men of Sarawak.

"Pepper did not make enough money because our village did not have the means to go and sell it to the merchants on the coast" he explains.

Whole generations of men hit the road for ten to fifteen years, for 500 to 1000 RM (120-240$) a year, cutting down trees with machetes in Sabah, breaking their backs in Brunei's petrol ports, or within the machinery of Singapore's gas industry for the most daring.

They came back every three years roughly, to visit their parents, get married and have children. Meanwhile, women were going to the fields, in the pepper, rice and rubber tree plantations. They brought up children and made their own mattresses and clothes. Every time the men came back, they had more and more tattoos.

Bunga Terung

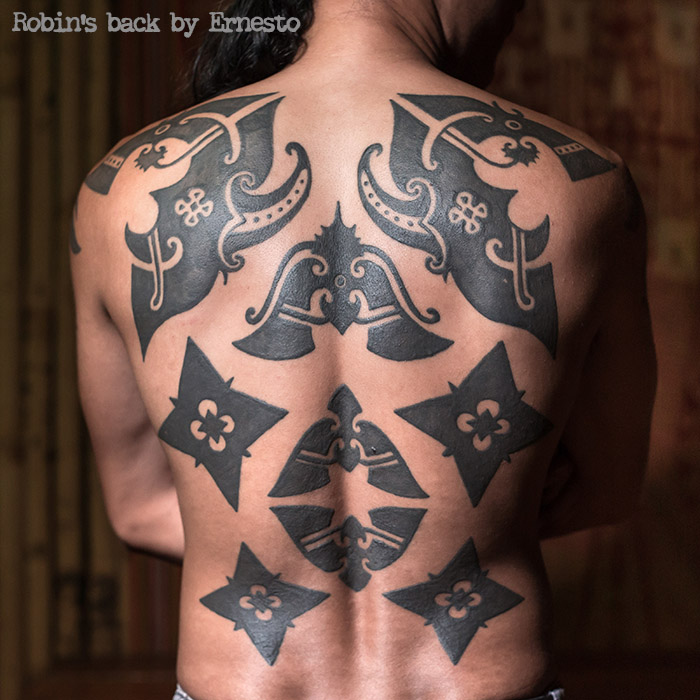

Traditionally, young Ibans begun with a couple of bungai terung tattoos, one on each shoulder. They are inspired by a local eggplant flower, called brinjal. The tattoo symbolised the passage to adult age, it signified a respect of the moral values of the village and signed the young man's departure for the belajai, the initiation journey.

These tattoos were opportunely placed by the straps of the wicker bag the young Iban was going to acry during his expedition to "discover the world". For a few months or a few years, he would walk from longhouse to longhouse, offer a hand for everyday chores, refine his knowledge of his own culture, listen to the elders, and in return he received tattoos. During the XXth Century this belajai turned into a temping pilgrimage from job to job, perpetuating the quest for social prestige. The more a man accumulated tattoos, the more he became desirable in the eyes of the women of the community. His marks were the symbols of surmounted obstacles and accumulated riches.

Iban tattooing from Borneo

His body would become a journal of his travels and achievements. It is a road book, a passport, a strong sign of identification, which allows Ibans to recognize each other. On Maja's arm, reads a phrase "Salamat kasih semua urang" which means "Thank you everybody", tattooed in the city of Julau. A memory of all the visited place, tattoos are exchanged against an animal or human skull, an amulet or a knife. Metal has a high value, as a basis to make weapons and tools, but it is also offered to the artists so their soul does not soften and they remain hard inside themselves. Strength is needed to tattoo whole bodies on the floor, with just two sticks.

"Four people were tattooing my back simultaneously for over ten hours. Not with ink but with candle soot. I drank a lot of langkao to endure the pain" Maja recalls.

On his back forms the tree of life, the story of his existence. At the top, two ketam belakang, a pattern inspired by the shape of a crab, which to him represents a rebate plane, the tool of woodwork, symbol of his years as a lumberjack. On the arm it is called ketam lengan. At the middle of the back a buah engkabang, a maple seed falling like a helicopter, the fruit from which Ibans extract butter and oil. At the bottom the four flowers complete the pattern in an aesthetic fashion. On his chest, Maja wears a small star... it's a plane, he explained.

"The first time I saw one flying over the jungle, it was a very mysterious object for us so I had it tattooed, in order not to forget". A great part of Iban beliefs and practices are linked to a free interpretation of the environment. In some villages, elders still listen to bird songs to help them make decisions on a daily basis, and make amulets with what they're inspired with in the jungle, stones and fruits being gifts from the deities.

For Rimong, 70, the star among the flowers on his back represents a precise emotion. "Because I loved looking at stars in the evening with friends. It's a memory that fills me with joy". For the tattooer as much as for the tattooed, the meaning of each piece gives ample room to personal interpretation. On his arm, Rimong wears a tuang, an imaginary creature from his dreams.

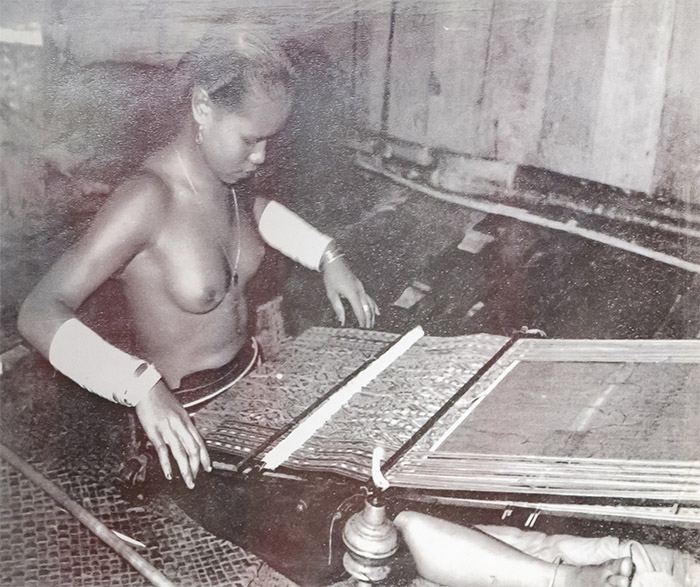

The tattoos are an echo of their spiritual beliefs, the patterns being inspired by the power of animals, plants and humans. Before tattooing, a chicken was sacrificed to appease the spirits and ask for the god's consent. Women of the community respected the same ritual before weaving a pua kumbu, the sacred textile used to wrap the heads freshly brought back by victorious warriors and by shamans before invocatory ceremonies. With the ngajat, a ritual dance, the pua kumbu is another strong piece of Iban heritage.

Like the traditional tattooer invoking the spirits to be guided in the realisation of a pattern, Iban women weaved images that their ancestors showed them in dreams.

It was the kayau indu, the "women's war", practiced for generations while men were cutting the heads of their enemies, to attract the god's favours during fights against other tribes and for the harvest of rice. The best weavers were thanked for their essential contribution to the well-being of the community with a tattoo on their fingers, or a pala tumpa, a circular tattoo on the forearms. Iban women wearing traditional tattoos have almost disappeared today.

Also rare now, the tegulun, a tattoo applied on the fingers of victorious head hunters, the only one to necessitate a religious ceremony. In spite of the peace treatises of 1874 and 1924 between the Dayak tribes, head hunting reappeared sporadically, to eventually disappear at the beginning of the 70ies.

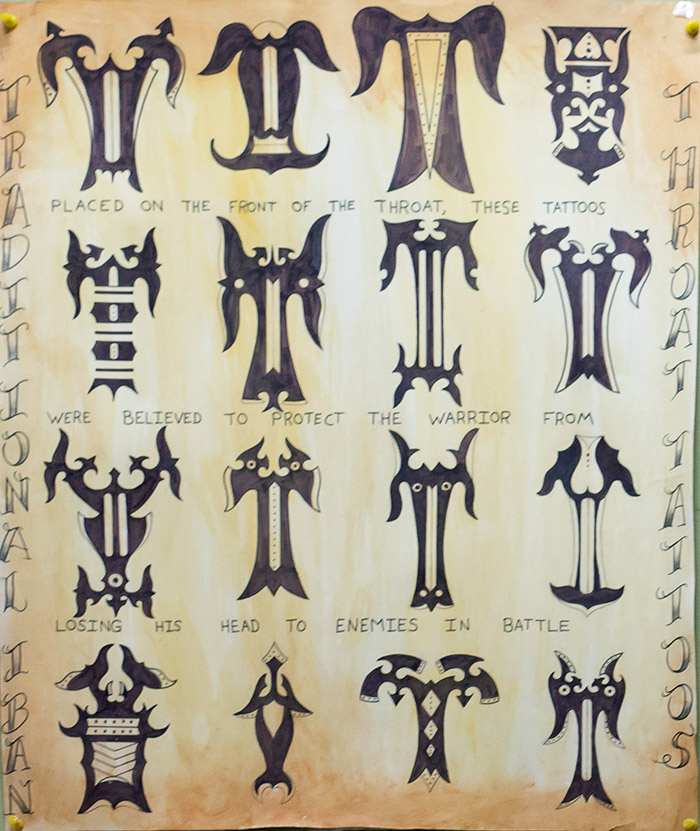

More common, the Ukir rekong, allegory of a scorpion or a dragon on the throat, symbol of strength based on the power of these animals. It protects the necks of warriors against the blades of rival tribes, while the back of the neck is protected by long hair. A good number of men share the motif of the fishing hook on the arm or the leg, a reminder of their activity as fishermen.

This whole cosmos was jeopardized when the Christian missionaries ventured into the jungle to impose the divine word in these villages which had been animists forever. In the kitchens, the gaudy portraits of Jesus and the Virgin Mary in 3D have become the only authorized decoration.

The forced Christianisation that started in the 60ies created a deep breach in these communities. Today, 80 to 90% of the inhabitants are converted in longhouses, some of them become priests, and most of them go to church on Sundays. A church to be found in each minuscule hamlet by the soccer field. In the long house Lenga Entalau, the missionaries arrived late, only fifteen years ago, but they made up for lost time with brutal measures.

All the elders were forced to burn their relics, amulets, remedies and skull-trophies bearers of life, or to throw them in the river. Some of them became ill at the sight of the brazier, as if their soul was consumed at the same time as their precious goods. Some resisted passively, hiding their last skull in a plastic bag at the back of a shed, or entrusting the objects charged with black magic to a son gone to live in the city.

Bryan did not give in. 97 years old and covered with tattoos, he worships seven deities, messengers between men and Petara, the supreme god, as well as the various spirits and ghosts that make the Iban pantheon.

Ibans during WWII

His tattoos protect him against strokes of bad luck. He is convinced of this since he heard a story during world war II. In 1940 some Ibans were enrolled in the British colonial army, where they formed the most part of troops assigned to the protection of the coast of Borneo against a Japanese landing.

A waste of time, since the imperial army occupied the island and gave the locals a hard time, starved, tortured and massacred them. A lot of them escaped in the jungle. At the end of the conflict, in collaboration with the Allies, they set up a guerrilla to chase the occupier: it was the Borneo Project.

Japanese soldiers dropped like flies under the hits of poisoned blowguns. Bryan was one of those rangers in charge of holding the line against the Japanese, who never managed to reach Ulu Skrang. "One day, an Iban regiment fell into a Japanese trap. The only survivors are those who had kept their amulets and had not converted to Christianity" he asserts.

Today, the young generation has distanced itself from institutionalised religion and a minority is starting to be interested in their ancestors' past.

This minority thinks that a degree is not enough to prove one's social worth. Facing constant attacks against native culture by religious people who want to model their soul, by politicians who want to suppress their idiosyncrasy, by business men who devastate their forests with bulldozers - and globalisation sweeping away everything as it passes by, the Iban tattoo is becoming a part of the culture again.

More a community than a ritual, more a sign of defiance against the times than a sign of appeasement destined to the gods, adapted to the taste of foreign visitors and sometimes emptied out of its spiritual substance, tattoos remain an important ethnic identification mark facing a terribly uniform world.

Going further

" Iban culture and traditions : the pillars of the community's strength " by Steven Beti Anom, a work of reference on the history of this people.

"Panjamon: une expérience de la vie sauvage", by Jean-Yves Domalain, The travel diary of a French naturalist who lived in an Iban tribe at the end of the sixties. Even though he was married to an Iban woman, tattooed and accepted by the community, he had to escape to save his life, poisoned by the village's shaman.

Sarawak (1957) and Life in a Longhouse (1962) by Hedda Morrison, a German photographer known for her pictures of the Beijing of the 30ies and 40ies, and of the Sarawak of the 50ies and 60ies. She lived in this region of Borneo for twenty years, and her photography missions in the district of Kuching granted her a rare access to numerous communities.

FIND THIS FULL ARTICLE ONLINE, PHOTOGRAPHS AND TATTOOS, ON APPLICATION ATC TATTOO

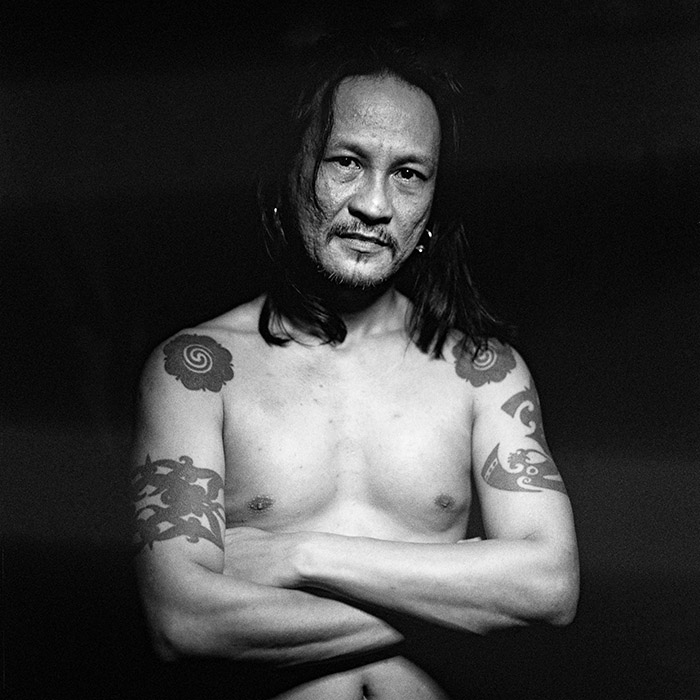

Ernesto Kalum, diehard Iban

Text : Laure Siegel / Photographies : P-Mod (article publié en 2015)

Part 2. Borneo Headhunters

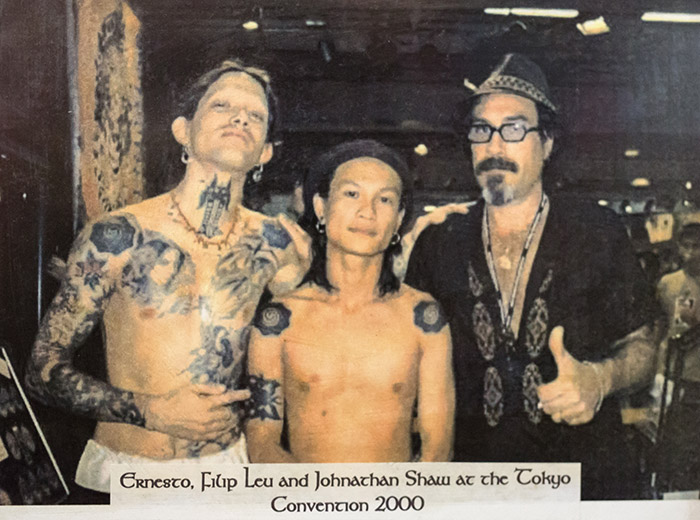

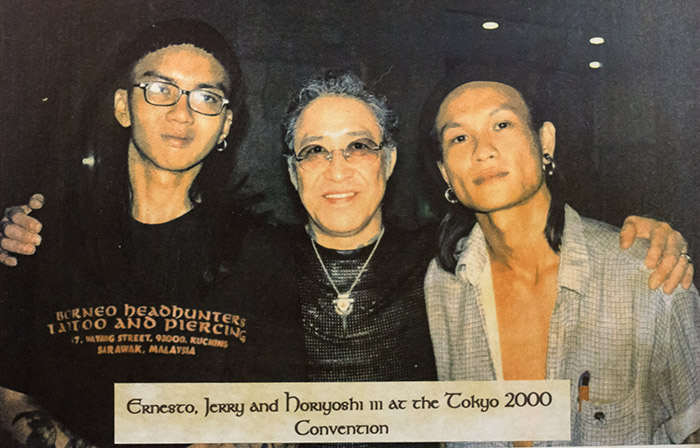

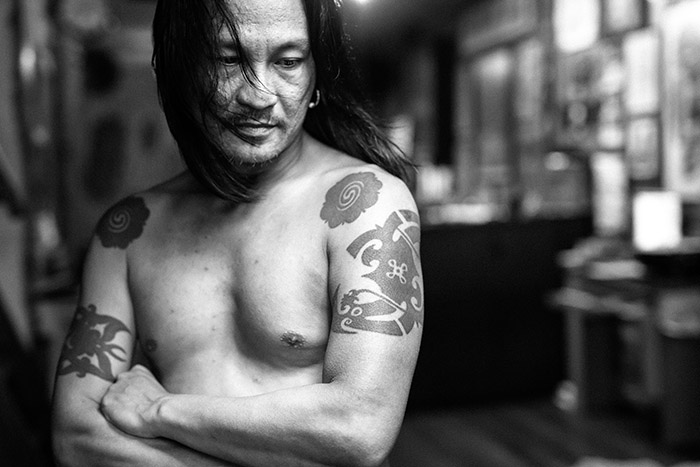

Fifteen years after having engraved Filip Leu's throat, Ernesto Kalum walked his own path, from international conventions to ethnological research, keeping out of fads and the mundane. For the local boy, Borneo's Iban culture is breathing its last breaths. However, he will defend it until the end, as he has done for twenty years. We met him in the Borneo Headhunters Tattoo Studio, his headquarter in Kuching.

Born Iban in Sibu 45 years ago, the civil servant's son was passionate about tattoos since he was twenty. " I wanted to get a tattoo but there was only one shop, specialised in old school (celui de Yeo, pp-). I started to tattoo myself, my first piece is this Superman logo on my calf." In 1998, after some experiences in the banking sector in London and the naval industry in Singapore, he decided to open a studio:

"There was no future for tattooing. I prayed every day that at least one client would come through the door and give me something to do. I spent my days drawing. It was very difficult for a young man from a tribal minority to shape his life in Sarawak. So I fled my country because there were no opportunities. »

Ernerto Kalum iban tattooer

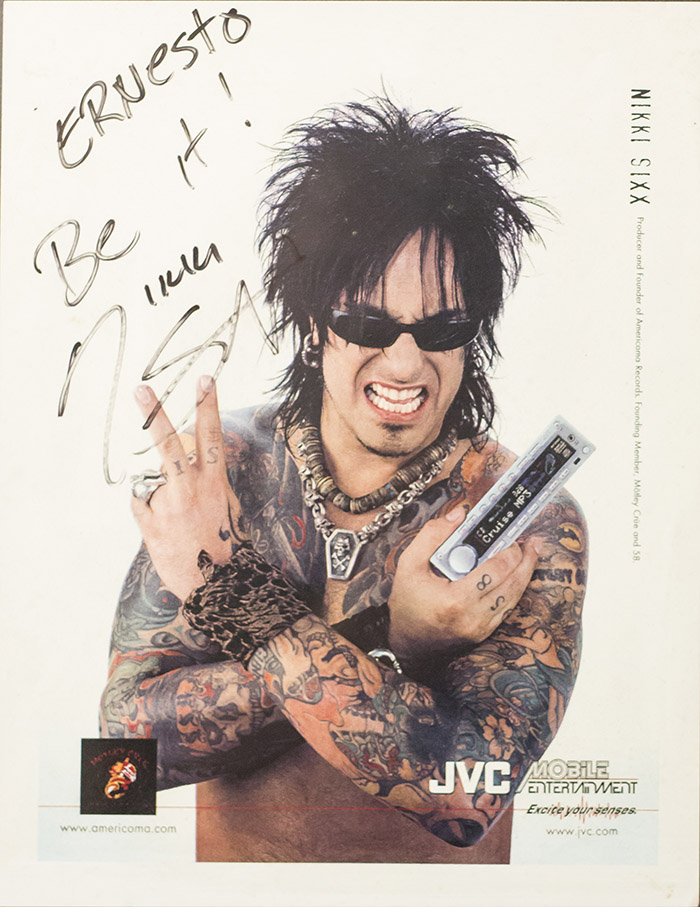

Two months after he had opened, he went back to Wolverhampton, a small town near Birmingham, where he obtained a degree in law a few years earlier. He was used to tattooing his mates for fun against beer and cigarettes. He finally exploited his gift for drawing and started his professional career as a guest at Spikes Tattoo & Piercing. He nicked rock'n'roll stuff, in the Mötley Crue inspiration, but his work on the Iban patterns he brought with him showed some real graft.

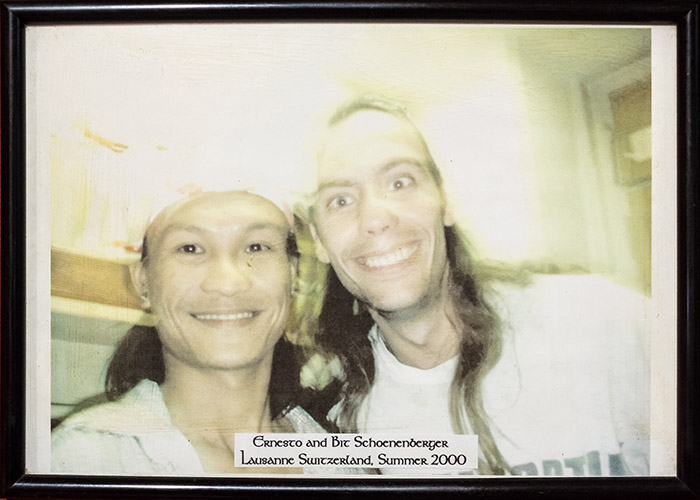

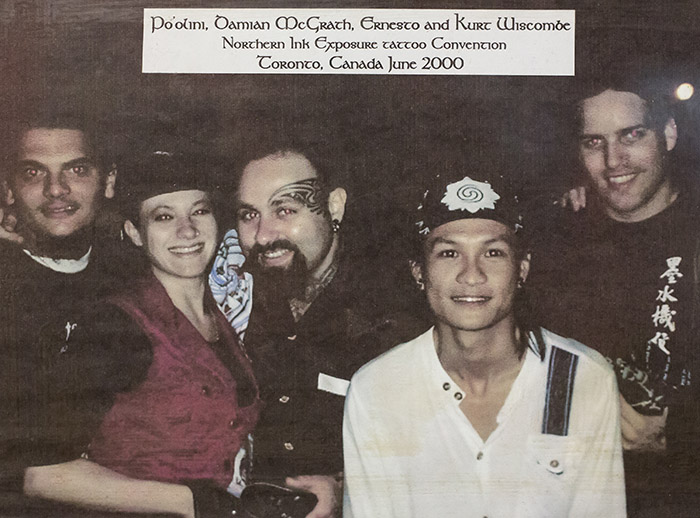

He stayed in Wolverhampton for a year, and cherishes the memory of a Mötorhead concert for a ten pounds ticket. He then applied for over 150 conventions. Only one answered, the one in Lausanne in 1999.

Lausanne Tattoo Convention, 1999

"I met them all then. Tin-Tin, Paul Booth, the Leu family... I thought that Filip was a musician, he looked like the Aerosmith's guitarist. I was innocent, I didn't know anything about the big names." He made friends with Bit Schoenenberger, alias Sailor Bit, and settled in the Swiss city for a year to work at Ethno Tattoo, in the shop of the guy who became his best friend.

He tattooed more and more Iban patterns, whose rise was favoured by the revival of tribal style, but always with a machine. One day Felix Leu arrived behind him as he was tattooing a client. "He took the machine from my hands and threw it in the bin, without saying anything, and he left."

Ernesto, who possessed the art but not the method for everything to make sense, went back to the jungle. "I had to understand my own culture, the very culture that my grand-father was not allowed to tell me about. At the time, the trend was to sweep away the past, to stop talking about these old-fashioned things, get a degree and find a modern job. I did the research myself with the elders who accepted to help me in spite of the pressure they were under. »

Hand Tapping comeback

When he came back to the city, he inaugurated his first hand-tapping. "It lasted a long time and the volunteer suffered a lot but the pattern was perfect. I was very proud." Drawing on his experience, he went back to work at Ethno Tattoo in the year 2000. The golden occasion was not long awaited. "

Filip Leu came, he looked at the images of the old tattooed Ibans that I always carried with me and he said to me "So you're going to tattoo me with this, right?" Ernesto did not feel ready to achieve what Filip urged him to do: the Iban scorpion on the throat, the same tattoo that his mother Loretta wears, done by his father Felix. Seeing his hesitation Sailor Bit did not beat about the bush: "If you do this tattoo for him, it will change your life. »

Felix wanted his son to be tattooed at the 34, the mythical headquarters of the Leu family on Lausanne's central street ." The former shop, it was a special place. Miki Vialetto was here, Felix Leu was here, everyone was here. It was really important for Filip to wear this piece and that it be applied in a traditional way. I really gave 120% of myself during these hours of work. It was a very spiritual moment." The day after, his career jumped and he now prays for his agenda to get lighter. "Everything changed. Everybody wanted me to tattoo them. In two weeks, I booked a year of appointments."

During those golden years, he rubbed shoulders with those who will become his main inspirations, the world figures who elevated tattoo to the rank of arts: Filip Leu (Switzerland), Paulo Suluape (Samoa), Leo Zulueta (United-States), Roberto Hernandez (Spain), Bit Schoenenberger (Switzerland), Horiyoshi III (Japan)...

Ernesto, Iban tattooer in Kuching

Ernesto talks about his call with deep respect: "Tattooing has been a lucky way for me to discover the world, in return we have to help preserve the reputation of tattooing".

In 2003, he felt that he had to come back to Kuching." I was always on the road, I didn't have the feeling of belonging to such or such place. My home was where I was happy." Isolated on his island, he also hoped to better control the crowd of clients. A waste of time, the shop was always full to breaking point, so he closed his door. He only tattooed on appointment, with a rhythm that allowed him to transmit a positive energy to each of his clients. His clientele was made up by 40% of collectors, 20% of tourists and 40% of locals.

Since 2008, he is assisted by 31 year old Robinson Unau. An architect and Ernesto's client, he quit his job to follow him. Ernesto chose him for his spirit. "It's hard to find people with a soul nowadays". But even the one who became his right-hand man still tattoos with a machine. "He feels he has to go in this direction and tattoo by hand but he doesn't feel ready to do so. We are working on it! »

Ernesto is dedicated to sharing his knowledge: as a speaker at Sarawak's museum, a counsellor in movie productions that comprise parts of the Iban culture, like the movie The Sleeping Dictionary, and as a producer of traditional music. He organised a first event in May 2002 in the cultural village of Sarawak, The International Borneo Tattoo Convention, and a second convention in 2007. "I just want people to be interested and that they know who they are and what they do. My community is right here but nobody listens, everybody wants to make money. I can only give some information to a few people, I am realistic."

He is not very optimistic about the survival of his culture, severely torn by years, forced Christianization and frantic globalisation. "Iban culture died with the generation of my parents. I still respect ancestral beliefs, but I got tattooed when it was already over. I am a museum specimen. We do not get tattooed to inscribe ourselves in the present, which is totally disconnected, but rather to reconnect with our roots. When there is nothing spiritual or religious left, in these conditions it is easy for a culture to simply disappear. Without culture, who are you? »

Without culture, what do tattoos represent? "People only want rock'n'roll. And you will always loose against rock'n'roll. In the past years, even the Iban tattoo has become rock'n'roll, and has lost a lot of its soul. We can't just ink anything anyhow, we have to keep parts of the original spirit. Ibans under 30-35 don't know much about their culture. All this knowledge disappears, in favor of TV sizes, car brands, or professional status and money in your bank account. It's a pity that it is such a waste, that we don't fight a bit more to keep some identity alive. The deletion process of aboriginal cultures is very brutal. »

To him, the preservation of a part of the culture is paradoxically intertwined with its opening to the world. "If I hadn't tattooed outside of this country, and hadn't gone to conventions abroad, people here would never have been interested in Iban tattoos. It's MTV's theory. It has to come out, to have success outside, and to come back, and it will be popular again... For me, it is not a contradiction that Iban patterns are tattooed by foreigners on foreigners. The Leu family drew inspiration from Iban culture for their floral patterns and that is very good. Iban means 'being human'. If the person is clear about their life's path, informed of the reason why they want this tattoo, no problem, I'll tell their story on their skin. »

Ernesto and Robin will be at the Paris international convention ("Mondial du tatouage") like every year since 2012. In the meantime Ernesto enjoys his daily life in his peace haven. Braided mattresses on the walls and on the floor, aligned books and VHS tapes, pictures of his path alongside the big names of tattoo, original drawings, arts and crafts from Borneo ...his studio is the result of a whole life that he has patiently built. But his city is changing, more "lounge" bars, more traffic, more air conditioned malls.

Ernesto is starting to think about retirement. "I am giving myself another eight to ten years in the job, and I'll retreat in the jungle, in my other house." He also has his throat to cover, which he leaves to Filip Leu of course, when the time will be right.

http://www.borneoheadhunter.com/

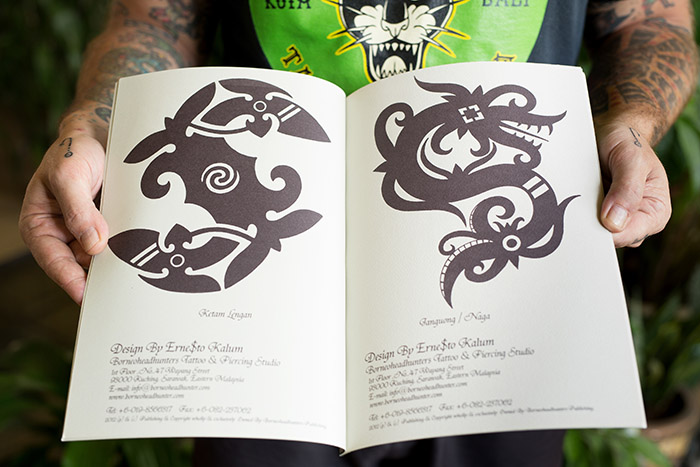

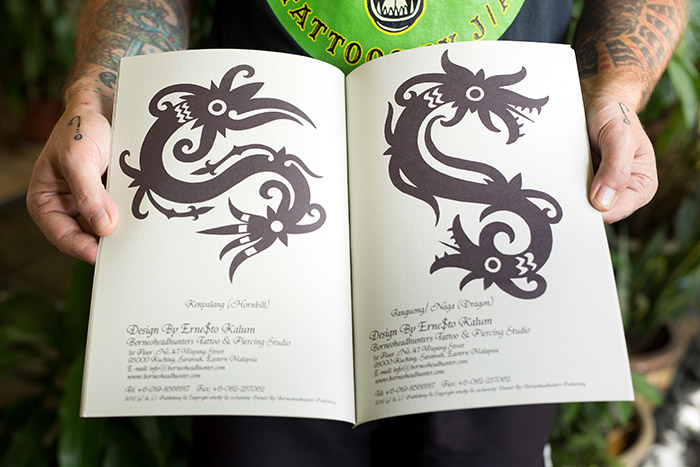

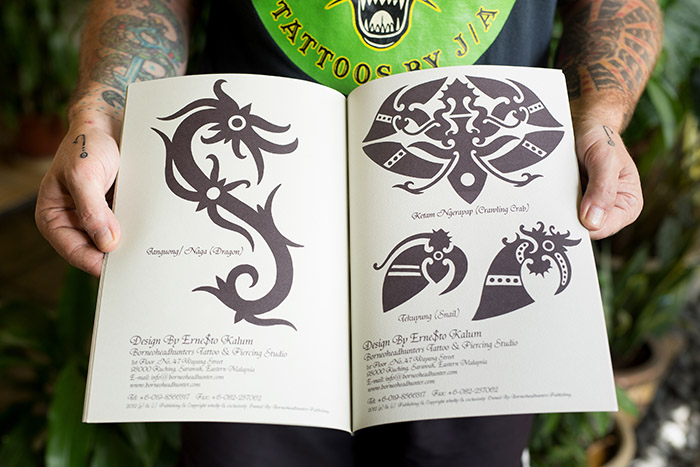

Ernesto made a book on the Iban tattoos. Here are a few examples.

FIND THIS ARTICLE IN FULL, PHOTOGRAPHS AND TATTOOS, ON THE APPLICATION ATC TATTOO

Chris Roy – The Death Row tattooist

Texte: Tom Vater / Traduction : Laure Siegel / Photographies : Chris Roy

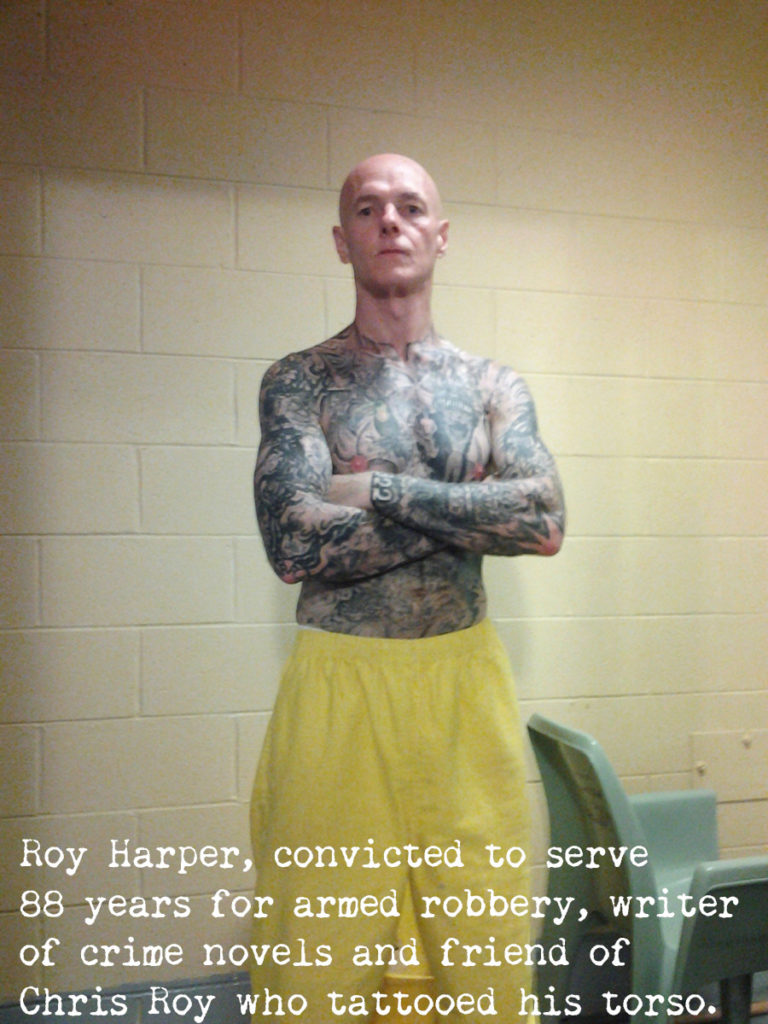

Chris Roy, convicted for murder at age twenty, has been incarcerated in a super max jail in Mississippi since 2001. Roy is Parchman Prison’s tattoo artist – the man who inks fellow inmates through cell bars with equipment made from next to nothing. His epic life journey from juvenile drug dealer to tattooist in one of the USA’s most brutal prisons is one of ruthlessness and bad luck, struggle and neglect, tenacity and discipline.

“I get along with the vast majority of guys I tattoo. But I have done plenty of tattoos on guys that I have no respect for, guys I've had deadly encounters with, and, if the situation had been reversed they would likely have tried to scar me or infect me with the viruses available on every zone… or tattooed a “Fuck you” on my back.”

I have been in touch with Chris Roy for more than three years now. Like me, he writes crime novels. But it is his career as a tattooist, a brilliant meditation on incarceration and identity, which drew me to his story.

“I was raised in the midst of ugly Gulf Coast beaches, thieving in communities of both rich and poor. Mom was an awesome Mom, but she had no help. It's no excuse, but that's why I began stealing and dealing - from and to the popular people with all the money.”

From the age of twelve, Roy started to work as a mechanic, first fixing his friends’ go-carts and dirt bikes for free, then working at his uncle’s salvage yard. But he didn’t last.

“I couldn't stand that adult mechanics who learned from me were being paid way more, and I needed better pay since my mother kicked me out. I left home with a motorcycle, jeep, boat, a pocket full of drugs and $600.”

Chris Roy, tattoo artist

By the time he was seventeen, Roy sold stolen or found goods and had spent time in a juvenile detention centre and a state military training school. He’d also trained in Taekwondo, kickboxing and boxing since the age of ten. Roy started with a school friend, Dong, the leader of the 211, a notorious Vietnamese gang in Biloxi, Mississippi.

“Dong was the main supplier to guys like me. He was an arrogant, violent dude, known for carrying weapons. After nearly two years of making a bunch of money, Dong and I had a huge misunderstanding. Our last encounter turned into a fight. I jumped him before he could pull a weapon. I knocked him out and he suffocated. I was really scared the 211 would retaliate, so I buried him.”

Roy was eighteen. Two years later, in October 2001, he was convicted of murder. In Mississippi that meant death or life without parole. “My crime, the result of a fist fight, would have been a manslaughter conviction with any attorney other than the public defender I was stuck with.”

The law is against Roy, who although guilty, got sentenced in an era when violent criminals were handed extraordinarily harsh prison terms. Pre-1995 murder convictions became eligible for parole after ten years. Convictions like Roy’s, handed down between 1995 and 2014, become eligible for parole when the convict turns 65. Someone convicted of murder today will get out decades before Chris Roy, who is not due to have his appeal heard until 2047.

After a couple of years in lockdown at Parchman’s Supermax Unit 32, Roy was transferred to General Population in the East Mississippi Correctional Facility.

“I met this guy called Tattoo in 2003. He’d been a tattoo artist out west for twenty years and he tattooed like a surgeon on amphetamines. He could construct a precision spec machine out of pens, cigarette lighters and radio parts in the time most people drink a beer. He was an arrogant asshole. But he became my kind of asshole, and after a couple years of black eyes and cracked ribs, he became a friend.”

Prison tattoo

Roy’s cell mate Gene talked Tattoo into lending Roy his machine for the night.

“The machine instantly became an appendage through which I could extend my senses. I could feel the suction and discharge of the ink, the minute vibration of the needle pumping and staining. I could sense that sweet spot depth of penetration that varies from thick to thin skin...”

The first tattoo Roy did was a rabbit with fangs, a cowboy hat and a double barrel shotgun.

“I remember guys at breakfast the next day, seeing the homicidal bunny. They all lined up to let me practice on them. That day, my life changed.”

Roy set his cell up like a tattoo studio, the walls covered in pages from motorcycle and tattoo magazines and original flash art. “I had medical supplies from the clinic. Free world inks. Even had a couple apprentices doing the grunt work. There was an endless line of customers in the thousand man facility. I've done lots of chest and back pieces, side and stomach, - and most of these were big, bad motherfuckers.”

Roy himself is not tattooed, “If I had tattoos I would go mad from obsessing over ways I could have done them differently or better.”

Naturally, prison authorities don't like their inmates inking each other. Some prisoners get serious infections, and gang tattoos have far reaching consequences for young inmates. But the US prison system and its employees are also inherently lazy and corrupt.

“I did tattoos on two guards and a male nurse. In return I was allowed to go into the clinic and get all the supplies I needed: latex gloves, ointment, iodine, even alcohol. The Chief of CID would escort me to any zone in the prison for 20US$ and leave me to tattoo. I made about $10 an hour. We were tattooing all night, smoking weed, jamming rock, fantasizing about what we would do once free.”

For a moment, it looked like Roy had carved out a life of sorts.

“I had a tattoo business that made money. I had an excellent job working for the Education Department teaching math and English in GED classes. I had a group of guys I trained in boxing and I enjoyed building props for plays. But every day, without fail, I planned to escape.”

In 2005, Roy made a break that was straight from a movie, sawing through the bars in his cell window with a hack saw. But once outside, plans went awry and he was caught within 24 hours. Shortly after, he escaped a second time. And got caught once again and returned to Parchman. For the next three years, Roy didn’t have a single opportunity to tattoo.

“I experienced the worst living conditions imaginable. Now a high risk prisoner, I was moved to a different cell every week. I was strip-searched and put in restraint gear every time I came out of the cell - even to the shower and yard cages. There were psych patients screaming, throwing feces, setting fires and flooding their cells. It was hell. I knew I would have to live like this for years. But that brief moment of freedom, the memory of it, made it worth it.”

Tattooing behinds bars

Things changed in 2008, when Roy qualified for a high risk incentive program.

“We had to figure out a way to tattoo while being watched on camera. We had this big rolling telephone, basically a huge crate on wheels, outside the cells. The customer would roll the phone crate in front of my cell, sit down on it, hold the handset to his ear, pretending to make a call, and stick his other arm into my cell. The phone blocked the camera's view.”

The hardest inmates to tattoo are those on death row. Kept on their own tier at Parchman, these men are almost impossible to reach. Contact with staff or other inmates is strictly forbidden.

“We made history when my friend D-Block paid an officer to allow me to tattoo him through his bars. It was expensive, but it was worth it. He showed off my work outside in the yard cages to others on death row. Nearly everyone wanted me to tattoo them, but they couldn't afford to grease the right palms.”

Roy managed to tattoo D-block six times.

“I also got friendly with a guy called Ben. He is up for capital murder and it’s not looking good for him. I put pictures of his wife, his daughter and his granddaughter on his back along with a winged horse and a goblin skull. I must have been up to his cell twelve times. But Ben suffered from paranoia and delusions. We fell out and he burned me for 500$.”

In November 2016, Roy was caught with a mobile phone and was taken out of the high risk incentive program. He spent ten months in a cell with a steel door in almost complete isolation and could no longer tattoo.

“I thought a lot about tattooing then. It’s what keeps me sane in here.”

Since he is back in his old block, he pursues the activity that puts him at the centre of his community and has tattooed a couple of large side pieces. Through the bars of his cell of course.

For more information on Chris Roy and his case, visit https://unjustelement.com/

Build a tattoo machine in an American maximum security prison

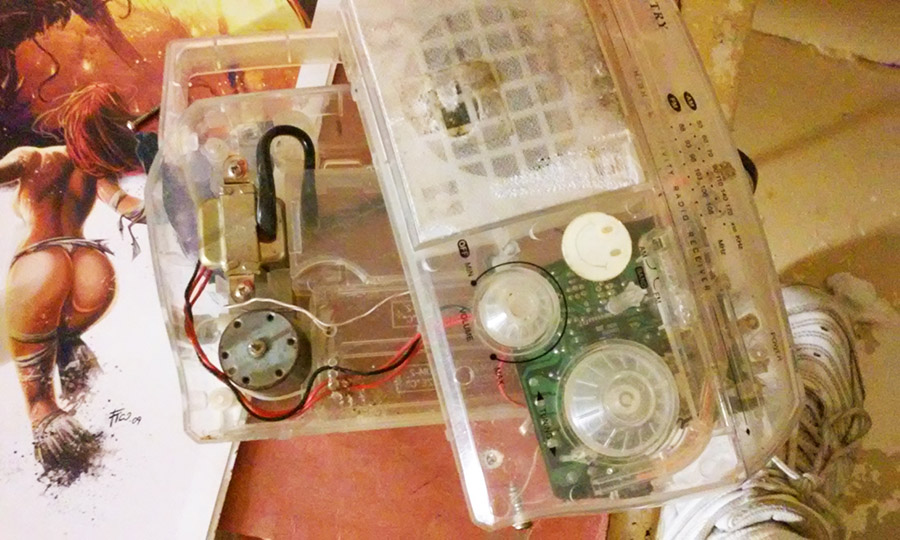

Roy didn’t have much to work with to build his tattoo machine in Parchman maximum security - a prison issued radio, a Bic lighter, a clear Bic pen body, an empty ink cartridge, a ballpoint tip, the rubber body of a security flex pen, the plastic top of a chemical spray bottle, and a small square of rubber.

Building the machine

“First I remove the ballpoint and replace it with the jet from the Bic lighter. Then I cut a small section of the flex pen body to insert into the motor end of the cut down Bic pen. This will hold the tube securely in the centre. The spray bottle top is a perfect motor mount. I cut it a little to slide it onto the Bic pen body. This makes adjusting the needle depth easy. Then I cut off the ballpoint and insert the jet from the lighter into the plastic tip. The square of rubber needs to fit onto the motor shaft."

"I poke a hole into the rubber next to the shaft and insert a small cut of insulation from telephone wire, the sleeve for the needle. The needle then fits into the piece of insulation. I then place the needle, the tip, the guide (the former ink cartridge), the ink cap (a soda pop top) and a wipe rag (a piece of t-shirt) in a bowl of water and boil it in a microwave for three minutes. Finally, the motor is secured to the mount with a rubber band and the machine is wrapped in Saran wrap.”

Producing ink

“I remove the blades from a couple of plastic shavers and tape the bodies together with salvaged tape. I glue a piece of A4 paper with toothpaste into a circular smokehouse that will collect soot. The shavers go in the centre and I set fire to the plastic heads. I cover the smokehouse with another piece of paper underneath a magazine. The paper will turn to soot which I collect in a bottle top. Burning two shavers makes enough ink for a very large tattoo.

Mixing the ink is an art in itself. I put water in a plastic bottle cap, then a couple micro drops of shampoo. I sprinkle the soot in a little at a time. Too much shampoo and the detergents will make the tattoo blue or green. Too much soot and the ink will not work in the machine's suction and discharge.”

Build a needle

The final necessary tool is a decent needle.

“I heat the spring from the lighter with a slow burning flame off tightly rolled toilet paper. I move the spring through the flame while I apply steady pressure, pulling it straight as I move it. If I pull too hard, it'll snap. If it gets too hot, it'll break.”

FIND THIS FULL ARTICLE, PHOTOGRAPHS AND TATTOOS, ON THE APPLICATION ATC TATTOO

Eloïse Bouton, the daily battle

Text: Laure Siegel / Photography: P-Mod

Freelance journalist, author and feminist activist, Eloïse Bouton questions our representations of gender. In an article published in 2015, Bouton, who enjoys getting tattooed asked an important, long overdue question: "Why do tattoo magazines continue to stick images of half-naked women on their covers?"

Maud Stevens Wagner (1877-1961), traveling circus performer and the first known female tattoo artist in the United States.

We talk about media, feminism, tattoo, music and the importance of images and words.

As far back as she can remember, Eloise has always been attracted by counter-cultures. As an adolescent, she dragged her sneakers into various cultural underbellies - she is a big fan of hip-hop and likes the radical aspects of tattooing. As part of her English studies, she undertook a research project on African-American feminism and civil rights movements in the United States. "I met a lot of women with thug life tattoos, prison-style. I was interested, there was always a story, a meaning. One day, one of these women showed me a documentary about Maud Wagner, one of the first American female tattoo artists. She was a circus performer and had her whole body tattooed. I was fascinated by the counter-cultural, political and feminist aspects of her life."

Eloïse Bouton, writer and Femen

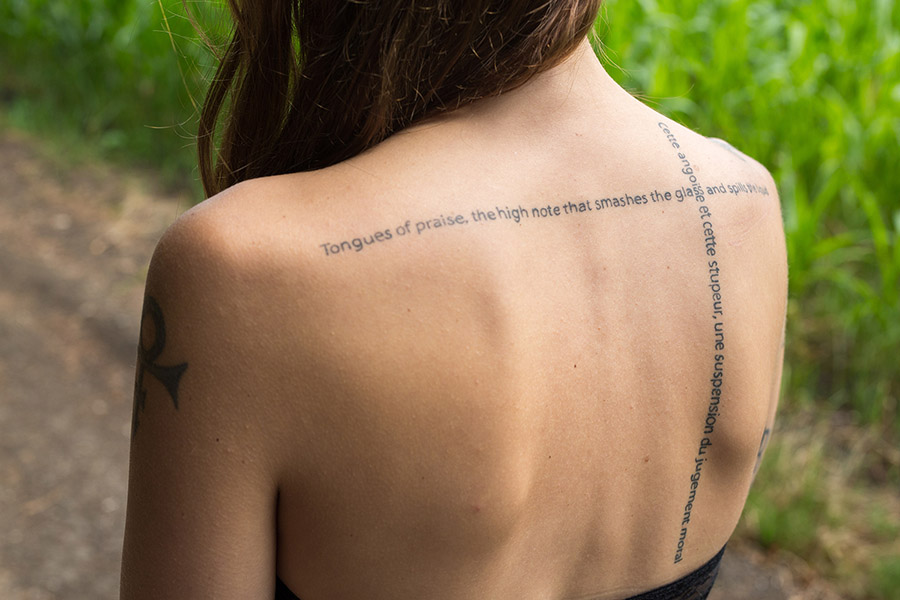

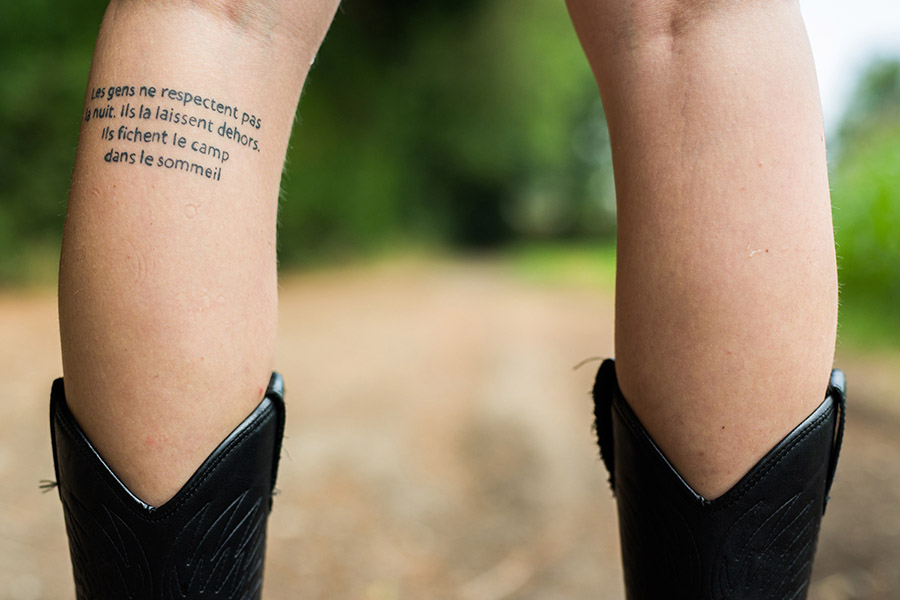

Eloïse first got tattooed when she was sixteen - "I lied about my age" -, and received her first piercing a little earlier. She covers her body, tirelessly: "The tattoo went along with my reflections on feminism, gender, body. It was a way to break the doll image I was projecting of myself, a white girl with long blonde hair and clear eyes, that hyper-normal side that did not correspond with who I truly was and with what I wanted to say. I didn't necessarily do it to piss off my parents. But I definitely wanted to piss off people in general."

Eloïse has nine famous women quotes tattooed on her body, from Angela Davis to Frida Kahlo through the punk band Kenickie, Tattooed by Dwam. (Nantes, France)

After she graduated from university, Eloïse started working as a journalist and quickly became aware of the necessity of feminism, everywhere, all the time. "I was initially involved in various feminist movements like The Beard ("La Barbe"), which denounces the fact that women are underrepresented in politics, culture and media. I was a freelance writer then specializing in music, and I was the only girl who wanted to write about hip-hop so I was told "Ok you're gonna do something about Beyoncé." I had a rock band, I was a professional hip-hop dancer, I’d written a thesis on it, I knew the scene well, but I was not credible because I was a girl." To be able to work, Eloïse broadened her field of expertise, from music to culture in general and then from culture to society, and more specifically to issues affecting women.

"Soft Porn Tattoo"

In 2012, the Femen adventure undoubtedly brought feminism back to life in France. Eloise created a national branch of the international feminist organization led by Ukrainian Inna Schevchenko. In November, a Femen action against the Catholic association Civitas, which had campaigned against same-sex marriage, took on incredible proportions. Media from around the world came to cover events where Femen were expected to turn up, if only to witness naked women take the street to scream their rage. With her right sleeve tattooed, black and red, Eloise was immediately spotted and banished from good society. "It totally killed me professionally.

I told my employers that I was still the same person. I was an activist before and everybody knew it, but I think that the nudity used by Femen touched something sensitive.But no one wanted to work with me anymore, even if I worked under a pseudonym."

Right sleeve tattooed by Entouane (Boucherie moderne - Brussels)

In spite of her years of militancy, the extent society’s will to control the bodies of women still manages to surprise her. "The weight of the church and of our Judeo-Christian heritage is still extremely strong in our society. A woman's body carries a pure and sacred dimension and must be transformed only because she carries a child or because she has her period and can have a child. But if you decide to strip naked when nobody asks you, and if you are strongly tattooed so that you have apparently disfigured your body in a vulgar manner to such a degree, that you interrupt a public event, and that in addition you carry a message that goes against all this, it is unbearable for a part of the population. We became the incarnation of sin."

In February 2014, Eloïse became the first woman in France to be condemned for "sexual exhibition" after she’s taken her top of in the Church of the Madeleine in Paris to campaign for the right to have an abortion. Since then, she has been fighting for reform of the sexual exhibition law which she considers sexist and she has protested against the de-politicization of her actions.

Combo "bad boy" et "hot chick"

Following her conviction, Eloïse left the Femen to regain her freedom and her breath. She again tried to find her place in the media world that had banished her for fear of her "polemic", something she perceives as contradictory, as the media feeds on polemic, "It is the paradox of this milieu. Now editors think I have legitimacy to write about women. I get more commissions again even if I take care not to be locked in this "feminist vigilante" box. But I really appreciate the fact that I have the opportunity to write papers with a strong ideological conviction. I did not have this opportunity before. »

In October 2015, Eloïse took shots at the tattoo press in Brain Magazine, attacking this niche media’s inability to evolve with time: "I wanted to understand why magazines perpetuated this debilitating soft porn vision that has nothing to do with tattoos anymore.”

At this moment, Eloïse was already angered by the burlesque pin-up shows common at conventions: "In counter-cultural circles, you expect people to be subversive, to challenge everything, but in fact many people fall back into even more normed patterns than those pervasive in general society. These people do not disentangle clichés as one would expect from them, but rather contribute to perpetuating them."

She also suspended her Suicide Girls account, a glamour website created fifteen years earlier whose mission was to celebrate alternative beauty. "All these hyper-young girls, not really tattooed or pierced, these close-ups of vaginas, the comments of guys under the photos, it had really gone bad ..."

It is necessary to go back to the source to understand the association of tattoo with female nudity. The first tattoo magazines were published in the mid-1980s by biker clubs with large amounts of spending money: "They created a very stereotyped image of genres, virile men and hyper-eroticized women. Until the middle of the 2000's, these magazines were sold on the shelves dedicated to pornography and contained erotic ads." The identity of the tattoo press, with its raw references to sex, social taboos and notorious underclasses, was forged: "It’s problematic that the nudity said nothing. A codified nudity with positions that are often submissive and hyper-sexualized. If these girls choose to go naked on their blog, it's not a problem for me, but in the specialized press, the only justification is to keep the commercial machine running and that's a problem. «

There’s a real danger that the tattoo media will no longer represent anyone anymore with this kind of gender representation. "The tattoo industry environment is changing, with more and more people coming out of Fine Arts schools and an ever-growing feminization in the milieu but the press remains blocked with this combo of ‘bad boy’ and ‘hot chick’ and continues to promote the image of an allegedly underground world that’s all of its own making. It is up to the tattoo milieu to discuss this and it would be important if the impulse to change were to come from within."

Eloïse is at the forefront of driving this discussion. With Emeraldia Ayakashim, DJ and sound designer, she founded Madame Rap, an online media that intends to reconcile rap and feminism and highlight the women who make urban cultures groove. She continues to be an activist, for big and small causes. "I am also part of a collective which fights to have the term Human Rights ("Droits de l'Homme" in French - "Men's rights") changed into human rights ("droits humains" in French), the battle lines are very clear, but the resistance we face is immense. Small things like this must be part of the debate. They are very important to raise awareness".

Her links :

"Confessions d'une ex-Femen", Eloïse Bouton (Editions du Moment - 2015)

"Les femmes en couv' des magazines de tatouage, l'apologie du soft porn" by Eloïse Bouton (Brain Magazine - octobre 2015)

For further information :

"L'art de tatouer. La pratique d'un métier créatif", Valérie Rolle, Maison des Sciences de l'Homme, 2013

Portfolio "Inked Girls"- Portraits de femmes tatouées, Laure Siegel and P-Mod

Cliff, craftsman tattooer

Text and Pictures P-Mod

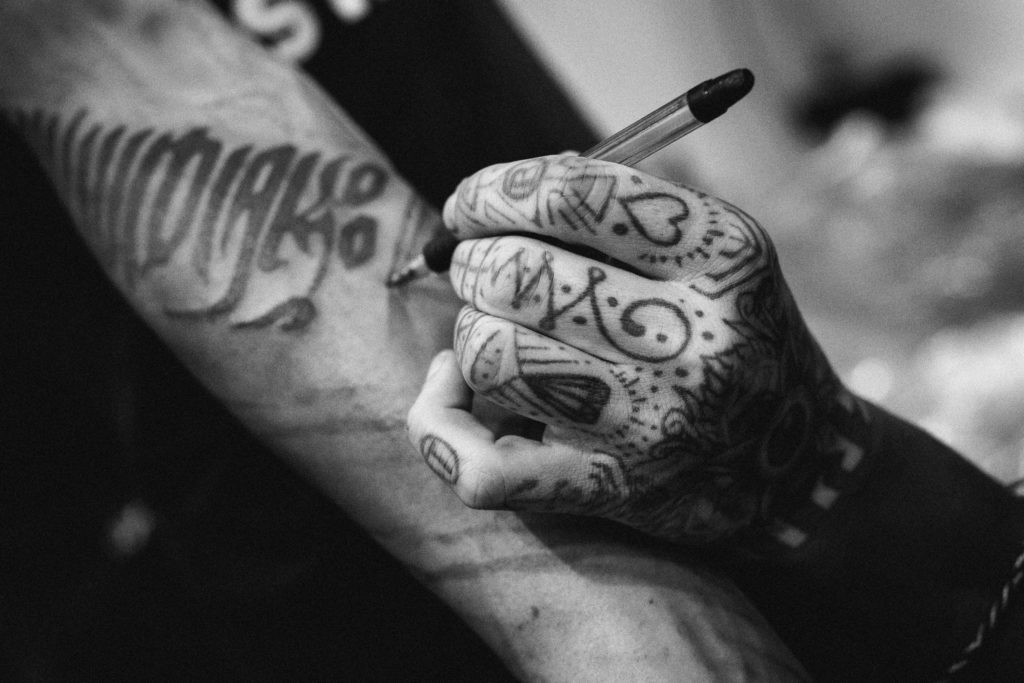

Two sticks topped with sculpted deities, one completed by a needle, the other used as a hammer: here are the Iban tattooers' only tools. Cliff, craftsman tattooer, passionate with traditional tattooing methods, makes them upon request in his Kota Kinabalu studio.

As he was living in Vancouver, Cliff, then 29, discovered hand-tapping tattoo as he visited the North American aboriginal communities who still practice it. He then lived in Papua New Guinea, where he pursued his discovery of tribal tattoo. Then, he got a sak yant tattoo, a sacred Thai mark on his hand, by Ajarn Man, based on the island of Koh Phangan.

In 2001, the 29 year old young man quit his designer job in the sector of video games at Electronic Arts and came back to his native land in the State of Sabah, north-west of Borneo. Since then, he has been tattooing updated Iban patterns at Orangutan Studio, a big shop with raw decoration, looking like a carpentry workshop, where he makes sticks sets.

The making of a set requires a machete, a week of work and a lot of precision. Cliff works with hard materials, like iron wood from Borneo, called belian in the local language, a red wood called belabah and an orange wood called sereya.

Berber Tattooing In Morocco's Middle Atlas En

Texte : Tiphaine Deraison / Visuels : Leu Family ©Seedpress

Immersion d'un rare détail dans l'art du tatouage Berbère Marocain, "Berber Tattooing In Morocco's Middle Atlas" est un témoignage unique. C'est aussi le résultat d'une série de rencontres fortuites. Le tout ensuite disséminé dans un récit d'aventures vécues par une famille bien connue de la communauté tattoo. Récit du voyage de Felix et Loretta Leu en 1988, il y a donc trente ans dans le monde rural et intime des femmes des tribus Berbères.

En 1988, quand la famille Leu pose le pied pour la première fois dans l'Atlas Marocain, ils sont accueillis par une famille locale, leur seul moyen de garder trace de cet art dont ils sont témoins sera d'apprendre, de reproduire et dessiner ces tatouages mais aussi d'en comprendre le sens et l'histoire transmise.

Berber Tattooing : une tradition orale du tatouage

Seule la tradition orale délivrée de femme en femme puis les dessins de Aia Leu rassemblés permettent une étude approfondie de cet art, ancestral que perpétuent les femmes berbères. Un tatouage traditionnel inscrit dans leur culture et leur vie quotidienne et capturé avec sensibilité dans cet ouvrage. Car cet art est en voie de disparition. Peu documenté il est aussi aujourd'hui de moins en moins pratiqué. C'est pourquoi, seules les plus anciennes générations en sont encore les gardiennes au savoir inestimable.

Hommage au tatouage, la famille, l'art et à ces femmes et issu des voyages de Felix et Loretta Leu, famille d'artistes, qui découvre le tatouage en 1978. L'ouvrage des Leu est, en conclusion, une source unique de documentation indispensable pour tout passionné de tatouage.

Berber Tattooing In Morocco's Middle Atlas

Felix & Loretta Leu

Illustrations par Aia Leu

Publié le 16 Novembre 2017

50 photos couleur 37 illustrations

42€

RETROUVEZ CET ARTICLE AU COMPLET, PHOTOGRAPHIES ET TATOUAGES, SUR L’APPLICATION

ATC TATTOO